It’s a first frost on your windshield kind of fall day. The sun creaks above the horizon and the frozen blades of grass quickly melt onto my shoes. Walking out among the mounds, I step back in time.

Built around two millennia ago — back when Julius Caesar and Jesus were alive and well — Native American earthen mounds and embankments were constructed up and down the Scioto River Valley in Ohio. People gathered at these huge geometric earthworks for feasts, funerals and rites of passage. They are preserved at the Hopewell Culture National Historical Park in Chillicothe.

I find the park sandwiched between two prisons on State Route 104, at the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains.

“It is a 2,000 year old cemetery. It’s a sacred place, that’s why we protect it,” says Shelby Heyen, park ranger. “All of it is fascinating; we’re constantly learning.”

Sacred, yes, but as I walk around the mounds, the sound of rapid gunfire erupts from one of the prisons. I find out later we’re near a practice gun range on the prison grounds. And then a large, loud, wailing siren breaks up the solemnity. I tell myself that it’s simply a daily morning siren, nothing to do with the gunshots. Again, I find out later it’s just announcing a morning prisoner count. Phew!

In the midst of all the nerve jangling noise, there is a quiet beauty appropriate for a burial ground.

“Once you’re inside the large square, it’s spacious and quiet,” says Myra Vick, park ranger and former biologist.

“We ask visiting school groups what one word comes to mind as they walk through the ancient site: ‘quiet, amazing, peaceful,’ are common responses,” Vick tells me.

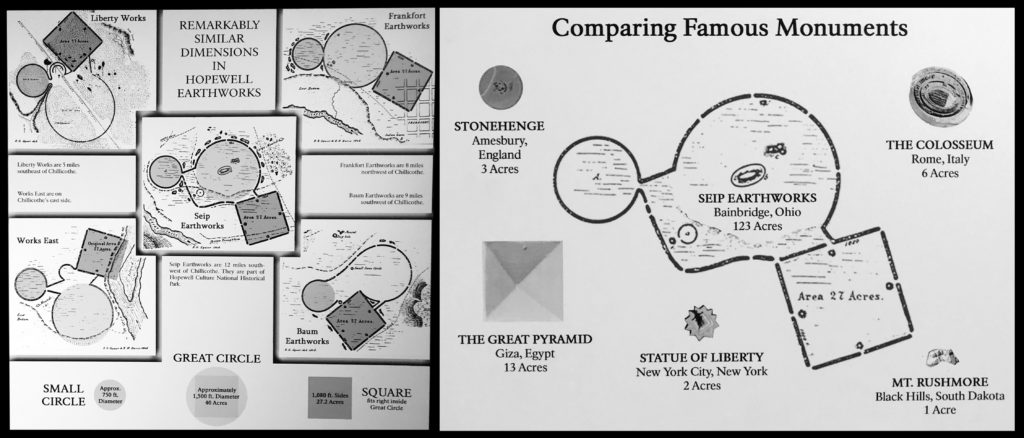

These giant geometric mounds adhered to a grand architectural design with squares, circles and octagons. They are the largest and most complex earthworks in North America, built by hand with thousands of tons of earth. The undertaking must’ve taken enormous amounts of time and dedication. They carried woven baskets of dirt and clay, shaping the mounds with freshwater mussel shells.

“There weren’t a lot of people in the area, so there had to be large gatherings over time to create these massive works,” continues Vick.

There is a fascinating uniformness to the layout of the sites — even 60 miles apart. In most, there’s a large earthen square, a large circle and a small circle. Measured out in modern days, the square would incredibly rest perfectly inside the circle by size! They encompass far more land size than Stonehenge, The Great Pyramid and The Colosseum combined.

The people who created these mounds were sky watchers and built calendars out of the earth beneath them. They measured astronomical events as well: certain sites even tracked the sun and moon through their phases.

Scattered among the sites are artifacts from across North America: from the Gulf of Mexico to Lake Superior, from Yellowstone to North Carolina. They show the tremendous range of early Native Americans. The Hopewell culture was based on hunting & gathering and they didn’t live in villages. For many modern tribes today, these are sacred places.

I love sites like these, places where our long-ago ancestors created enigmatic (to us) structures. Pondering why the ancient people are called Hopewell — thinking it’s some positive mindset reference — I laugh to myself when I find out it’s because their mounds were first excavated on Mordecai Hopewell’s farm back in the late 1800s.

“I like being outside,” says Vick,“It’s different every time. Being out here is a reward in and of itself. This is our office.”

Near the end of my visit, another long siren wales. “That’s the all clear; prisoner count successful,” Vick explains.

There is clearly so much we don’t know or can’t understand about the ancient people who once lived here. I love that it’s preserved though, even with something the ranger called “interpretive mowing.” This is my fifth visit to an ancient Native American site within a year and I am nothing but fascinated and intrigued.

The rangers are too. “After all the archaeology and scientific inquiry, it’s still a mystery: that’s what I love about it,” Vick concludes.