Remembering Our Earth,

Even in a Wooden Bowl

What is spiritual is what is most ordinary,

The common threads of hope and mercy

The things we know best

Because we have lived them all

So I chant the turn of another day,

Spinning grace into the world

Spinning the four directions until they turn like a wheel.

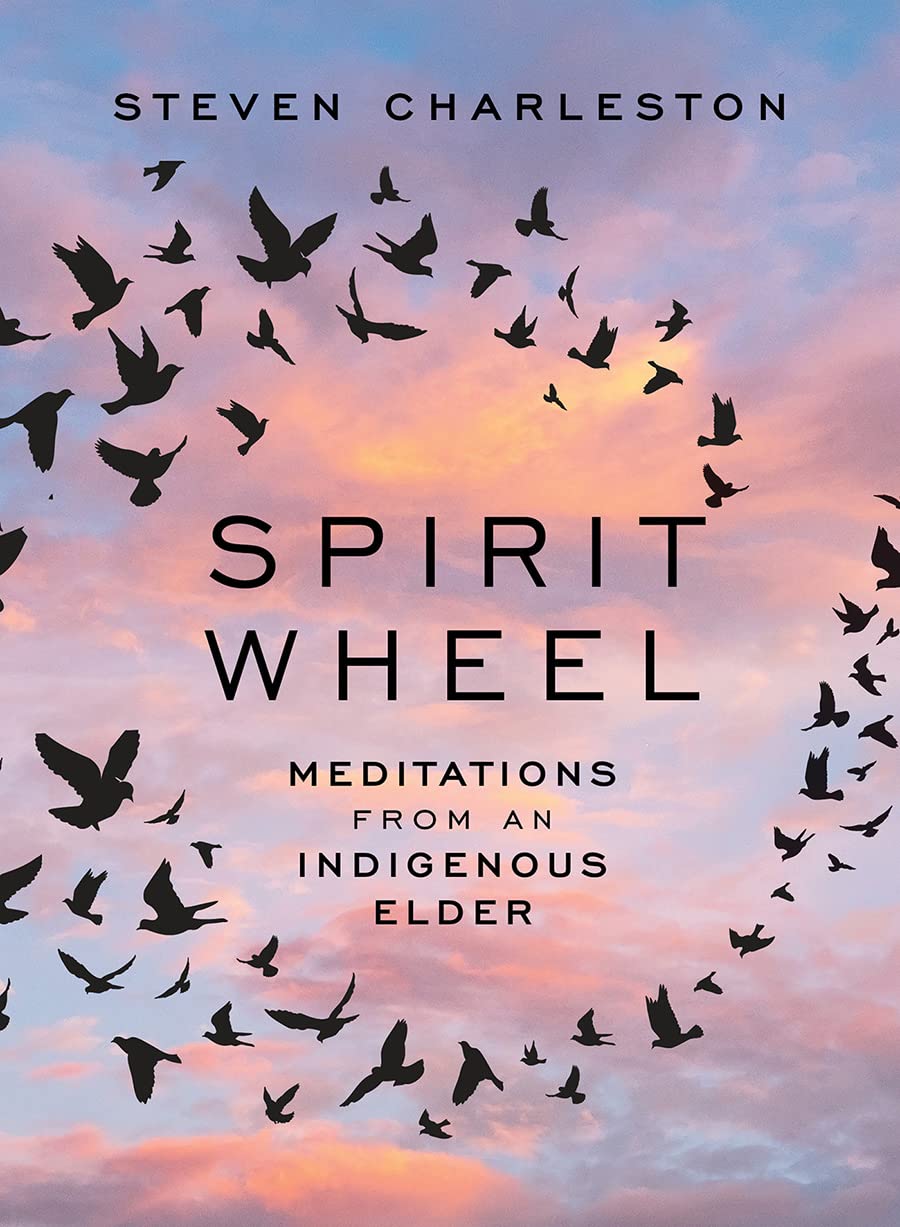

from the opening page of Spirit Wheel—Meditations from an Indigenous Elder

By DAVID CRUMM

Editor of ReadTheSpirit magazine

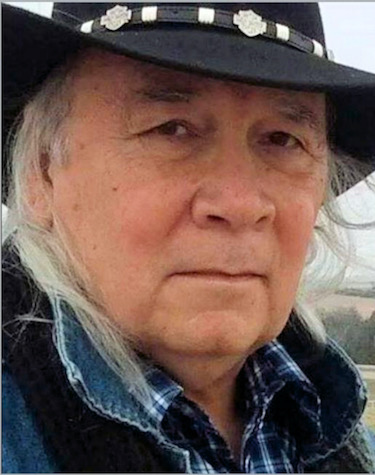

If you remember anything from this profile of the venerable Native American religious leader Steven Charleston and his new book, Spirit Wheel, remember two images:

A hand reaching out to feel a mound of soft brown earth in a wooden bowl

And an old man with long white hair sweeping the floor at dawn.

“These are simple things,” Steven Charleston told me in a Zoom conversation about his new book of meditations. “My life is very, very simple now. I don’t travel and give talks or do workshops anymore. I guess you’d call me sort of a contemplative—and this is by choice, much of it by virtue of my family.”

Among Native American spiritual leaders, Steven Charleston is truly a noble elder, widely respected for his work over many years. Like two thirds of the millions of Native Americans living today, Charleston is Christian by choice. He’s part of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma with his family roots in the Trail of Tears. He graduated from the Episcopal Divinity School in Massachusetts in the 1970s and became such a highly respected leader in the Episcopal church that he served in the 1990s as the Bishop of Alaska. He has worked on bridge building efforts across the worldwide Anglican Communion. Among his dozen earlier books, he is especially noted for a pair of 2015 books, The Four Vision Quests of Jesus, and a collaborative volume by 10 Native leaders writing on the theme: Coming Full Circle—Constructing Native Christian Theology.

He’s a spiritual leader, teacher and author who has touched thousands of lives around the world.

‘The Path My Ancestors Followed’

But, today, you might envision Steven Charleston in his Oklahoma home sweeping the floor. A

“I follow a traditional way of life now—and part of that is because of the importance of my family,” Charleston told me. “My father will be 100 years old in December. My mother will be 97 and I am the sole survivor to help them. I spend much of my day helping them and helping my wife, who has MS and also just got through a struggle with cancer. So don’t think of me as way off on some remote mountain top in some romantic vision of a spiritual leader. Think of me washing dishes, sweeping floors, doing laundry and taking care of my family. This is the path that I am on. This is a very important path. It’s less visionary than people might imagine, but it’s the path my ancestors followed—and it’s what I will continue to do.”

And what about the image of a small pile of earth in a wooden bowl?

Following Native tradition, Charleston prefers to pray and meditate “outdoors standing two feet on the earth so that I am reconnected,” but he also is aware that many men and women are not mobile enough to go outdoors or, even if they can go outside, they may not be able to stand. So a work-around he suggests is taking some soil—some earth—and placing it in a bowl so that you can reach out and touch the earth as you pray.

“Of course, I prefer to go outside and stand on the earth as I pray, so I am connected to the earth,” he said. “But I also am very much aware of all those who cannot take even those steps. So, just a small bowl of earth, natural earth, can remind us of the source and substance we come from. Just placing your hand on that earth can be a connection with our source. It may sound like a small affectation—this little bowl of earth—but it can be a very profound reminder of our connection to the earth.”

The Balance of ‘Social Determinants of Health’

In our conversation, I told Charleston that I was deeply moved by his expressions of Native American spirituality, because they echo so many of the other authors we have published over the years. That is especially true in books like Now What? The Gifts and Challenges of Aging that explore the full range of the Social Determinants of Health. That phrase refers to a growing body of global public-health research that illustrates how health and wellbeing are the result of far more than access to medicine and medical treatments. Health and wellbeing begin with simple, daily, human connection.

As I explained the harmony I hear between his teachings—and Native wisdom in general—and the emerging Social Determinants of Health, Charleston nodded in agreement across our Zoom screen.

“Thank you for sharing it in that way,” he said, “because it helps people who may be new to Native American spiritual thought to see how important and constructive Native tradition can be. There are things that Native people have been saying for centuries that everyone is now realizing are are very helpful at this time. This wisdom speaks directly to our culture and society and all of the things with which we are struggling around the world. As Native people, we believe that, embedded within us, is this ancient wisdom that not only speaks about interpersonal relationships with each other but also our relationship to the earth—and the need for dramatic efforts we must make to try to restore our balance.”

Too often, men and women seeking inspiration and renewal from Native sources focus on the more spectacular sights and sounds of famous spiritual centers around the world. In that “romantic vision,” as Charleston describes it, they miss a wisdom that can light up every aspect of our daily lives.

A Path of Patience and Love

“The truth is that so much of our mature spirituality is not the dreamy, romantic, visionary ideas we might have imagined in our youth,” Charleston said. “A lot of spiritual life is about hard work and persistence and willingness to do jobs that are not easy and are not quickly accomplished. The spiritual path I am talking about involves patience and love. Even in the most humble ways, my path is always to be helpful to others. We need to become accountable to one another. The more we practice that kind of spiritual path, the healthier our society will become.”

I said to him, “The authenticity of daily living runs throughout your new book—and all of your books that I have read so far. These meditations in Spirit Wheel are a gateway to far deeper truths. In fact, an invitation to ponder these more timeless truths is right there on the first page of your book when you call us to focus on ‘the deeper threads of hope and mercy.’ ”

He nodded again. “The saints of old—and certainly the elders in our Native American tradition—teach us that we should hope for our spiritual lives and our daily lives to be the same.”

Discovering Global Connections with Our Creator

This Zoom conversation echoed experiences Charleston has had throughout his more than seven decades on the earth. He says his own spiritual awareness began at age 4 among his extended family and community in Oklahoma. He eventually felt a calling to Christian leadership and became a seminarian in the Episcopal church. He recounts the revelation of these connections that he felt even as he began those seminary studies in the 1970s in the opening pages of Coming Full Circle:

This Zoom conversation echoed experiences Charleston has had throughout his more than seven decades on the earth. He says his own spiritual awareness began at age 4 among his extended family and community in Oklahoma. He eventually felt a calling to Christian leadership and became a seminarian in the Episcopal church. He recounts the revelation of these connections that he felt even as he began those seminary studies in the 1970s in the opening pages of Coming Full Circle:

In 1973 I sat in a seminary classroom as a new student preparing for ordination in my Christian denomination. The professor was explaining why the religious worldview of ancient Israel was so unique. He told us that no other people of that time had come to an awareness that God was singular; monotheism was the special province of Israel’s spiritual development. Moreover, he explained how this understanding had been woven into an even deeper theology that connected the tribes of Israel to God through a covenant, a promise of a land reserved for them, and the vision of a national identity as God’s chosen people. This, he told us, was the unparalleled story of the Old Testament, the term common in those days for what we have come to call the Hebrew Covenant.

As I sat there, I kept thinking to myself, “But I have heard this story before. This is nothing unique.” In fact, it is quite common because it is shared by many tribes, many peoples, who have a memory of themselves as a People, chosen by the one God to inhabit a special land and to be in covenant relationship with their Creator. It is the story of my own ancestors. It is the “old testament,” the traditional theological story of many Native American peoples of North America. I was only a first-year student in those days, too shy in my own education to contradict my professor, but now, many years later, I realize that the vast majority of seminarians still have not heard the other half of the story of monotheism. There is a complementary theology to the testimony of ancient Israel, an ancient theology that arises out of another promised land. There is a story of the indigenous nations chosen by God to dwell here, in North America, over centuries of our spiritual development.

In Charleston’s view of the world, God has reached out to men, women and children in many ways over thousands of years—and our spiritual lives will only reconnect with and hopefully repair God’s larger community if we can open our eyes to that larger vision of the earth.

What’s in This New Book?

This book is all about opening one’s eyes and ears—in fact, all of our senses—in daily meditation. Charleston calls his practice prayer, but this book is voiced so that readers of any religious tradition—or of no religious affiliation at all—can enjoy these one-page reflections.

Part of Charleston’s daily spiritual practice is writing down descriptive lines, or sometimes micro-stories, or sometimes Psalm-like pleas or celebrations. Some of these arise in his dreams, which he has trained himself to recall and jot down when he awakes. Some of them are the direct result of his morning prayers. Some are the thankful—or sometimes troubling—sighs of a man who has seen so much of the world that he now sees new spiritual facets in the most common tasks of daily life.

In the opening pages, he explains “the mystery of this book” as: “Somehow, I believe, the words you find here will speak to you. They will not only make sense; they will rise up out of your own experience. They will not be telling you something you did not know but rather something that has been part of you forever.”

Across Zoom, I told Charleston that my own favorite meditation is one that I have read, re-read and re-read again. It’s called “The Spirit Lives Next Door”

I still have trouble believing the Spirit lives next door.

I thought Spirit lived far away, in a gated community.

But at times I find the Spirit shuffling around next door

Early in the morning, coffee cup in hand

Looking a lot like me.

Spirit waves, I wave

But this neighbor Spirit

Disconcerts me with such nearness.

Until I need a favor.

Then I am glad the Spirit lives nearby

And is always home when needed.

I peep over the fence for a chat

A time to borrow what I need

And never be asked to return it.

As we came to the close of our hour-long conversation, I asked Charleston how he hopes this book will shape the lives of his readers.

“Motivated,” he said, pausing a long time after that one word. “Motivated is the word that describes my hope. I hope that this book motivates people in any number of ways. It can be motivation to action, to getting out into the world and taking their spirituality with them to join the struggle for preserving the earth. Or it may motivate them to become a more kind and patient person—to motivate people to value the truth and have that kind of authenticity in their daily work.

“At the end of the day, I don’t think I’m giving people anything they don’t already know. I am trying to help readers find those places that are already there in their lives. That sense of transcendence and connection is there in all human beings. Finding those and releasing those are a part of life. That’s what my writing is all about.”

.

.

Care to Learn More?

Get Steven Charleston’s books! There are so many places to start. This week, we are recommending his newest book of daily meditations, which allows readers to begin to practice the kind of long-term, day-by-day prayerful reflections that are such a foundation in Charleston’s life. So, please, visit Amazon and order a copy of Spirit Wheel—Meditations from an Indigenous Elder

If you want to dig deeper into Native American reflections on connections between Christian and Native traditions, you’ll want to read Coming Full Circle—Constructing Native Christian Theology.

Or, you may want to pre-order Charleston’s upcoming We Survived the End of the World: Lessons from Native America on Apocalypse and Hope, which will be released on September 19, 2023.

Want to learn more about connections with Social Determinants of Health and community-based wellbeing?

Order a copy of the very helpful and inspiring book, Now What? The Gifts and Challenges of Aging.

Want to learn more about the many other Native American issues our magazine has been covering?

Check out these stories:

Water Walkers series: Carol Trembath debuts her latest Native American book ‘Pass the Feather’

Bill Tammeus on: ‘Land Acknowledgment’ is a first step toward justice for our Native American neighbors

And: In Native Echoes, Kent Nerburn returns from Indian country with A Liturgy of the Land