Jews gather at the Western Wall at sunrise. It is traditional to stay awake all night in Torah study for Shavuot, and in Jerusalem, this all-night study is followed by gathering at the Western Wall. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

SUNSET SATURDAY, JUNE 8: Greenery and flowers adorn synagogues tonight, mimicking the top of Mount Sinai, as Jews wrap up a seven-week period of anticipation known as the Counting of the Omer. The Counting of the Omer ends and gives way to Shavuot, the celebration of the day G_d gave the Torah to the nation of Israel at Mount Sinai. Due to the counting of seven weeks leading up to Shavuot, this holiday is also known as the Festival of Weeks.

FREEDOM: FROM PHYSICAL TO SPIRITUAL

The ancient festival prompts many stories and interpretations. One of them emphasizes this: The movement from the Counting of the Omer to Shavuot connects the physical freedom in the Exodus with the spiritual freedom of the presentation of the Torah. During Passover, which was weeks ago, Jews acknowledged the physical freedom given to the ancient Israelites through the Exodus; more specifically, this physical freedom was acknowledged on the second day of Passover, when the Counting of the Omer began. Each night since, observant Jews have remembered the current count of days until they reach day 49. Today—day 50—Jews recognize the official presentation of the Torah. This, the 50th day, is also sometimes called Pentecost, although the Jewish religious associations with the holiday are different than the Christian Pentecost.

Did you know? Shavuot is one of the Jewish observances that differs, depending on location. In Israel, it’s one day; in the rest of the world, it’s two days.

OMER, GRAINS AND FIRST FRUITS

Ancient Israelites marked the spring grain harvest for seven weeks. (“Omer” is an ancient unit of measure.)

When that first harvest ended at Shavuot, farmers would bring an offering of two loaves of bread to the Temple of Jerusalem. In the same manner, the first fruits of Israel (Bikkurim) were brought to the Temple on Shavuot. In a grand display, farmers would fill baskets woven of gold and silver with the Seven Species—wheat, barley, grapes, figs, pomegranates, olives and dates—and load the glittering baskets onto oxen whose horns were laced with flowers. These oxen and farmers would travel to Jerusalem, marching through towns and met by music, parades and other festivities.

To this day, many Jewish families display baskets of “First Fruits,” including foods of wheat, barley, grapes, wine, figs, pomegranates, olives and dates.

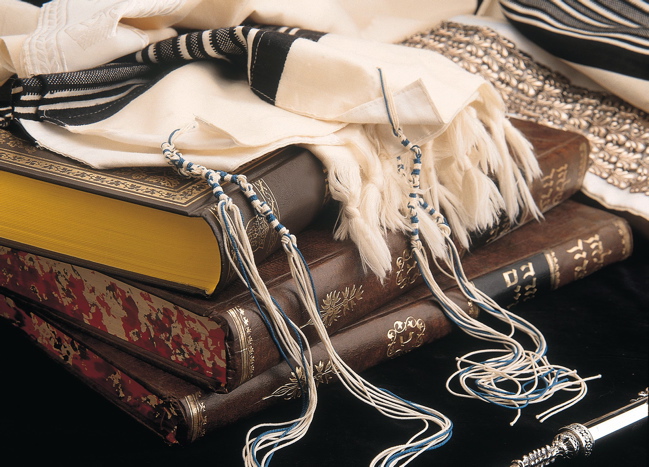

SHAVUOT: DAIRY, RUTH & ALL-NIGHT TORAH STUDY

Among the many customs associated with Shavuot are the consumption of dairy products and the reading of the Book of Ruth, along with, for many observant Jews, an all-night Torah study. Several explanations exist for these traditions. One is that Jews recall the night the Torah was given and how the ancient Israelites overslept; although Moses had to awaken the ancient Israelites, Jews today remain awake throughout the night, all the while giving thanks for the Torah. In Jerusalem, the all-night Torah study ends with the procession of tens of thousands to the Western Wall at dawn.

Work is not permitted during the entirety of Shavuot.

Looking for dairy recipes to prepare for the holiday? This Jewish blog offers Kale and Mushroom Quinoa ‘Mac and Cheese,’ and Haaretz suggests Yam, Goat Cheese and Rosemary Quiche.

For more holiday inspiration, enjoy …