Like Native American prophets voicing hope in the midst of trauma, Charleston asks us—

‘I hope you will see this as a personal invitation to join me and millions of others.’

By DAVID CRUMM

Editor of ReadTheSpirit Magazine

Are you afraid our world is ending?

Polls show that millions of Americans are fearful of the growing effects of climate change, of the rising tide of violence in many forms, of the impact of “wars and rumors of wars” and of the threats to democracies in many parts of our world. A vast number of us living on the planet share a growing sense that an irreversible “apocalypse” is on the horizon that is likely to change the lives of our children and grandchildren.

That also means millions of us are wondering: Where is hope?

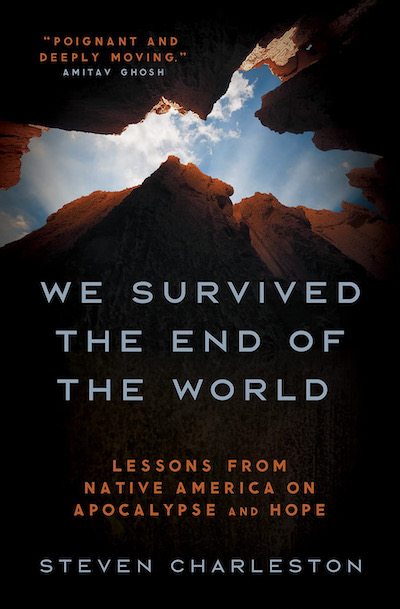

The venerable Native American theologian, teacher and author Steven Charleston reminds us that there are neighbors living among us across North America who—as resilient communities of people—already have survived an apocalypse. His new book is aptly titled, We Survived the End of the World—Lessons from Native America on Apocalypse and Hope.

Just to be clear about this book’s focus: Charleston is referring to the relentless North American genocidal campaign waged by European immigrants against this continent’s original communities. That genocide has ranged from outright murder to the theft of homelands to the long-term policies in the U.S. and Canada of kidnapping Native children and sending them to brutal (and sometimes deadly) boarding schools that attempted to wipe away all memories of their families and their cultures.

In the opening pages of what may be the most important book he has ever written, Charleston writes, “Native American culture in North America has been through the collapse of civilization and lived to tell the tale. My goal is to investigate how my ancestors were able to do that—and what their experience can teach all of us who are living in uncertain times.”

Then, to be clear on a second point: Charleston is saying that our earth already is in the midst of cataclysmic change.

In 2021, our publishing house launched the book God Is Just Love, subtitled Building Spiritual Resilience and Sustainable Communities for the Sake of Our Children and Creation. In that book, author Ken Whitt, a nationally known Christian pastor and educator, wrote about the kinds of knowledge families should be sharing right now about grassroots health, well-being, spiritual practices and resilience because—in Ken’s view—the whole world already is moving through a catastrophic tipping point. In fact, in his book, Ken, who is not Native American, urges his readers to learn from our Native American neighbors about survival in this time of turbulence.

Now, in this new book, Steven Charleston—the former Episcopal Bishop of Alaska, an elder in the Choctaw Nation and a widely quoted Native voice in American media—is saying the same thing.

“Apocalypse is what we are living through,” he writes in his opening pages. “It is the coming true of our worst fears.” We already have crossed enough environmental trigger points that devastating storms and other ecological disasters will continue to unfold—unsettling millions upon millions of new refugees with each passing decade.

The great value that Charleston provides in his new book is what Ken Whitt—and many other wise writers and scholars—have been urging us to consider over the past decade: Charleston has filled this book with Native American wisdom on how a people and a culture can hope to survive the end of one’s world.

This new book shares the visionary wisdom of four real-life Native American prophets—all of whom have living legacies within Native communities—plus wisdom from the entire sweep of Hopi culture—plus, a final call to action from Charleston’s own wisdom as a prophetic elder. In less than 200 pages, Charleston has given us a crash course on this broad-base of indigenous wisdom—from a total of seven Native sources—that will be fresh news to the vast majority of American readers.

‘Cracking open the ability of people to cross boundaries’

The first step toward finding hope and building resilient communities is a clear vision expressed in an honest message.

In our interview, I summarized for Charleston how I was going to open this column. I asked him if I was accurately conveying what he hoped to achieve in this book.

“Yes,” he said, “I am saying that we’re already deep into the midst of change and, now, each of us could play a prophetic role.”

I replied, “So, by using that word ‘prophet’ to describe these great Native American sages in your book—you’re not using that word to describe someone who can predict the future. I find that a lot of Americans confuse the word ‘prophet’ with some kind of ‘futurist’ or ‘psychic’ or ‘seer.’ Your ‘prophets’ are people who are speaking important truths about the catastrophic eras in which they find themselves, right?”

“Yes,” he said again. “When I invite people to become prophets, I am literally asking them to accept the reality we can see in our world today—and then tell others honestly what we see. I’m trying to crack open the ability of people to cross boundaries and to talk to one another and share what they are seeing in the real world around us. That is the prophetic experience that those of us living in an apocalyptic time are trying to develop.”

I countered: “But our readers might ask, ‘How can you expect me—an ordinary, flawed, stressed-out person—to be as prophetic as you are with all of your academic degrees and experiences as a leader? How can we aspire to be prophets?’ Our readers might complain, ‘We’re way too flawed as individuals!'”

Then, Charleston summarized a central theme of his book in a few sentences: “We have to understand that the kinds of prophets I’m talking about don’t start out as anyone special. A person who becomes a prophet is often reluctant to be chosen for this role. Initially, they may not want to carry this burden. The prophets I’m writing about were everyday persons who transformed from the clay of their everyday lives into rather extraordinary people we remember today.”

Christians and Jews who have studied their scriptures are familiar with this foundational truth about the ancient “prophets” we share: Many were reluctant, most had obvious flaws and some were widely disregarded by their neighbors for most of their lives.

When I made that point in our interview, Charleston responded: “You’re not going far enough in your description. Some prophets actually were reviled because of their past behavior. The story of a prophet is a person who—despite those flaws, despite those mistakes and despite whatever their neighbors think about them—begins to speak truthfully about what they are seeing in the world around them. As they begin to speak, they find that their vision is something that they simply cannot contain. Their message must come out.”

Charleston continued, “That’s the key thing to understand about prophets: It’s something that any one of us can become. That’s why my invitation at the end of the book makes sense. With the right time, the right circumstance and the right depth of faith, any one of us can stand up and proclaim what we believe to be the reality of our situation—and we may find that others will share that vision.”

‘People who were broken or confused find themselves transformed’

In this column, we won’t cover all of the seven prophetic figures profiled in Charleston’s book—four individuals and then the Hopi nation as a whole, plus some of Charleston’s own prophetic reflections.

But here’s a good example of a major Native American prophet with a living legacy today: the Seneca spiritual leader whose name is rendered in many ways today.

He’s called Ganiodaiio in Charleston’s English rendering of his original name—or sometimes his name is spelled as Sganyodaio, Ganioda’yo, Skanatalihyo, Conudiu or, as Wikipedia has literally translated his name: Handsome Lake. In at least one other new book about Native American religious groups, his chapter is titled by none of those names but by the word “Longhouse,” because his teachings mainly are preserved by followers of the larger Iroquois Confederacy, also known as “People of the Long House.”

“How do you pronounce this prophet when you talk about him to audiences?” I asked Charleston.

“I’m not a Seneca speaker, but I pronounce his name gah-nee-oh-DAY-oh,” he said. “His legacy is long and I think it is very important for readers—especially readers who are non-Native—to understand that we are talking about a living religion that still is being practiced. His story is not known today to most Americans, nor is his story very well known to all Native people across this continent—but I can say that, across Native America, at least his name is recognized and respected.

“This is such a key point I am making in the book: Our Native culture is not some dusty matter for historians and anthropologists to study. The Native religious world view is an ongoing, contemporary, modern expression of human spirituality—a religious tradition like Islam or Buddhism or Hinduism. We are not a matter of history. I wrote this book to bring awareness that Native people—and our Native religious wisdom—is very contemporary and very future-focused as part of our global dialogue on spirituality.”

He continued, “I am at pains, whenever I write or speak, to tell people that these ancient parts of our indigenous cultures not only have survived, but are continuing to flourish especially as we cross into these difficult times.”

I asked Charleston to give us a very brief summary of this prophet’s life.

“Well, the first thing to understand is that he was a broken man—a person who had just about reached rock bottom in his life largely due to alcoholism. He was restored to health and strength by some mysterious spiritual encounter that released through him a powerful spiritual message that transformed his people. That is the prophetic role we are talking about here throughout all world culture and all of the living faith traditions—people who have been broken or confused or were trying to run away can find themselves transformed by a spiritual force to provide a message that breaks through to the world. This is part and parcel of the apocalyptic experience.”

Avoid ‘the Baloney’ and pick up the ‘seeds’ Charleston is offering

One thing Steven Charleston is not recommending is that non-Native readers try to convert to indigenous cultures. “There are lots of books and programs and retreats by people who claim to have taken the wisdom from Native people and recast it as their own mix of Native American branded herbs or drumming or visions—or whatever else they are selling. And, to all that stuff you can buy from people who aren’t Native American—I say: ‘Avoid all the Baloney!’ Native people don’t want non-Native people to come and appropriate our rituals as their own.

“In this book, I am sharing a deeper wisdom. I wrote this book so that readers—especially non-Native readers—can see that anyone—and I mean anyone from the vastly different cultures around our world—can learn the truth about our tradition. Even though we went through the end of the world, we survived because of the wisdom of our prophets and the strength of our spiritual vision.

“You don’t need to take our rituals. You can find this wisdom, and your own visions, from your own culture. Instead of trying to sell Baloney—I’m trying to inspire prophetic leadership from every community around the world. In this book, I am offering seeds that can give people the confidence they need to avoid hiding in spiritual bunkers as the apocalypse unfolds. I want people to know that there have been crises like this since the time of the Ice Age. Humans have had to deal with apocalyptic crises since the origins of humanity.

“We’re living in an age right now when people are deeply fearful. I want to show people one option they could choose based on Native experience to find new strength. If we do, we can make a real difference. We can prevent this feeling of helplessness and feel, instead, both hope and empowerment.”

.

.

Care to Learn More?

Read our earlier interview with Charleston, headlined: Native American elder Steven Charleston’s ‘Spirit Wheel’ weaves spirituality from ‘common threads of hope and mercy’

Read Steven Charleston’s books! There are so many places to start. This week, we are recommending his newest book: We Survived the End of the World—Lessons from Native America on Apocalypse and Hope.

If you want to dig deeper into Native American reflections on connections between Christian and Native traditions, you’ll also want to read Coming Full Circle—Constructing Native Christian Theology.

Want to learn more about the many other Native American issues our magazine has been covering?

Check out these stories:

Water Walkers series: Carol Trembath debuts her latest Native American book ‘Pass the Feather’

Bill Tammeus on: ‘Land Acknowledgment’ is a first step toward justice for our Native American neighbors

And: In Native Echoes, Kent Nerburn returns from Indian country with A Liturgy of the Land

This is so helpful. Not only is the ice melting. The world has broken the ice. An additional resource for me is “Radical Hope: Ethics in the Face of Cultural Devastation.” by Jonathan Lear psychoanalyst and philosopher at the Univeristy of Chicago. He tell the dramatic story of the native Crow and how their leader brought them through the end to a new beginning of their society and culture. I see that Lear has a new book “Imagining the End: Mourning and Ethical Life.” By the way, he has been deeply welcomed into the Crow people.

Thank you for this ‘must read’ article. Prophecy at its finest.

Thank you for highlighting the wisdom of Steven Charleston. He has been an inspiration for many years, and I look forward to reading this new book of his. I, too, believe that we are at the end of one civilization, and the beginning of another, and in great need of prophets.