Want to learn more about this national conversation? Click on this snapshot from The Atlantic to read Steve Inskeep’s full September 1, 2020 story: What Lincoln Knew

By DUNCAN NEWCOMER

Host of the ‘Quiet Fire’ series

This is Quiet Fire, a reflection on the spiritual life of Abraham Lincoln and its relevance to us today. Welcome.

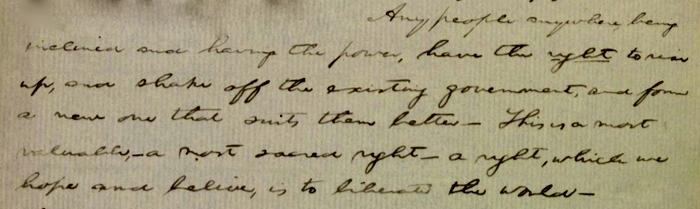

Here’s a Lincoln quote for you, which I’ve condensed for you:

“Let every American….swear by the blood of the Revolution, never to violate … the laws of the country (my bold) … Let reverence for the laws be breathed by every American mother to the lisping babe that prattles on her lap—let it be taught in schools, in seminaries, and in colleges…let it be preached from the pulpit…and enforced by the courts of justice. And, in short, let it become the political religion (Lincoln’s italics) of the nation…”

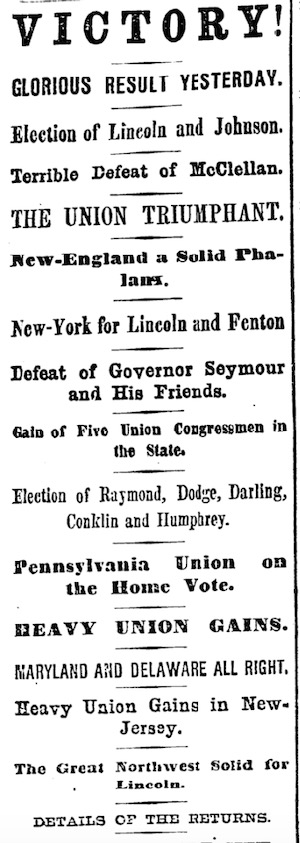

People are still quoting this speech from 1838. He gave it to the Young Men’s Lyceum in Springfield, his first invited public address. He’s 28. Yet just the other day the Governor of South Dakota misquoted this speech as if it’s about government protection of private property.

Thankfully, acclaimed author and radio host Steve Inskeep answered boldly in The Atlantic. I, myself, took to the airwaves in Maine a few days ago, feeling the relevance of this speech. We’ve been talking about the relevance of Lincoln’s spiritual life up here on Maine radio for about five years now. Even the current President seems, as Mr. Inskeep noted, to have a fondness for comparisons with Lincoln

But, as scripture can put it, “as far as the East is from the West so far”—so far is Lincoln from this current President. And as the Psalmist continues could we wish for our transgressions to be taken so far from us. Especially the transgression Lincoln had in mind in this speech, lawless violence against Black lives.

Lincoln discovered the end point of our transgressions. That discovery was Lincoln’s spiritual gold. Our transgressions are taken away from us by the righteous wrath and merciful justice of the Living God in the blood-cost of the Civil War. By the time of his last major public address Lincoln transcended his political religion of law and order with the wisdom and charity generated by our suffering. Slavery was our transgression and we have had to pay for it.

How did Lincoln get to such theology in a mere 27-year spiritual journey from the Springfield Lyceum to his Second Inaugural Address? “Lincoln offers an example of moral depth and subtlety that is hard to find elsewhere in American politics or for that matter American Literature.” so concludes John Burt in Lincoln’s Tragic Pragmatism. He balanced prophetic moral stances with a human sense of tragedy and irony, what history is really like.

But since law and order is on the front burner, once more, let’s try to understand how even Lincoln, as an ambitious young lawyer, split the difference between Abolitionist disorder and white lynch-mob lawlessness by appealing to one basic: Law.

When he first came to politics, devotion to the Law was his was spiritual life.

You could say that, as a spiritual person, Lincoln had to grow up from his young man’s fantasies of American greatness and his sole faith in law and order. And he did.

He paid for his wisdom with melancholy and was rewarded with compassion. In this first speech, however, Lincoln is not depressed. Nobody has ever said he was bi-polar, but he’s pretty high in this his first-ever major public address. And he’s going to give it all he’s got. He’s got a lot to give. The law really is his political religion. It is his spiritual life at that time.

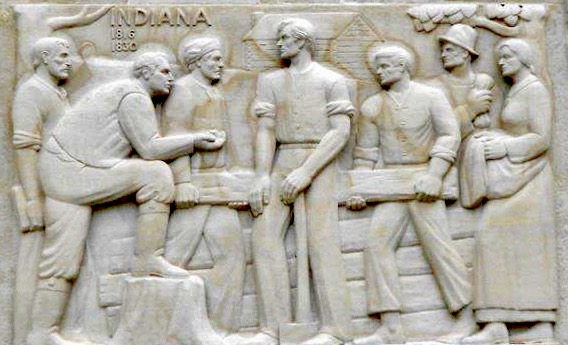

He’s a struggling young lawyer in the new state Capital, Springfield Illinois, a city of dusty or muddy streets, wooden walk ways, running amuck pigs , horses everywhere and great exuberance for this new nation, America, the United States, barely 50 or 60 years old itself depending on how you count its beginning.

So you have to figure this: Lincoln is almost 30. The country is almost 60. He is half the age of the new nation, the nation is just twice as old as he is. Everything is that new.

This situation gives the words “these uncertain times” a real ring. Not only is this new government really new, it is almost the laughingstock of the Old World, Europe thinks this democracy idea is a fool’s errand. This is not an errand in the wilderness with a beacon on a hill shining back freedom to the old world, it’s, to them, a flickering candle, a smoke signal.

Lincoln is in a pressured position as he gives this speech. It has the marvelous title “The Perpetuation of Our Political Institutions.” He was invited by the prestigious town debating society called the Young Men’s Lyceum.

Lyceum is a word from the Roman and Greek heritage that the frontier people keep hoping to use to bless their new project. Athens would be a popular town name and Athenaeums and Lyceums would be popular elite conclaves for the pillars, young pillars, of society.

Surely there must have been a saloon down the boardwalk from the church, often such meetings happened in churches, where most likely this evening meeting was held.

But the setting is even more perilous than we have allowed so far. Lincoln has been in the militia. Many of Lincoln’s companions in the law had been fellow militia members with him in the Black Hawk War aimed at driving the seriously beleaguered Native Americans back up into Wisconsin territory. Worse still, it was a time when most assuredly Black lives did not really matter. All up and down the Mississippi River, down in Alton, Illinois, into Louisiana, lynching and killings were rampant. The Presidency of Andrew Jackson had released what Lincoln and his Whig Party followers called mobs and were threatening institutions of America with Jacksonian mob-acracy.

To Lincoln this was not what America was for. The rule of law was the source of democratic government, it led to economic growth and social freedoms and stability.

Now this is where the spiritual life of Lincoln comes into play. Every one of his listeners would have known of the recent killing of journalists and clergyman Elijah Lovejoy by a pro-slavery mob in Alton, Illinois. Lincoln dare not say his name for fear of arousing the Abolitionists movement that Lovejoy supported. Lincoln was not that radical. His default position was what he called that “political religion,” love of the law, absolute total obedience to the law in every respect. So much so that by the end of this speech Lincoln is saying that no one should ever even walk on the grave of George Washington and the “proud fabric of freedom” should rest as the rock that has been like the church of Christ able to withstand the gates of hell.

Well. Lincoln learned a lot in his spiritual journey, and he learned not to mix his metaphors, with fabric and rock and church all rolled into one really manic law and order passionate plea. Remember, he’s young. He’s just starting out. He does not have a traditional religion. He doesn’t go to the Presbyterian church as a member. He is not a river rat either, nor just a storekeep or a day laborer taking a raft down the river. He is looking to build a life and help build a country and he knows, or hopes, that the reasonableness of law abiding people will do what the passions of the revolutionaries did: create a democracy.

Twenty seven years later Lincoln will have a full spiritual life and message and will empathically share with the nation in its sorrow over the Civil War and he will invoke love and mercy, righteousness and courage, a living God, and a devotion to peace and justice among ourselves and with all nations.

In the spiritual life of Lincoln we see fire early on and then we see a quiet fire were law and order take place along with peace and justice, charity and righteousness, and the humility of a people who have been chastened even punished by a Living God.

That is the arc of a spiritual life that can be seen in Abraham Lincoln, and it can be for us, as for him, a way to live on in honor, down to the latest generation.

This is Duncan Newcomer, and this has been Quiet Fire. The spiritual life of Abraham Lincoln.

.

Care to Enjoy More Lincoln Right Now?

GET A COPY of Duncan’s 30 Days with Abraham Lincoln—Quiet Fire.

Each of the 30 stories in this book includes a link to listen to the original radio broadcasts. The book is available from Amazon in hardcover, paperback and Kindle versions. ALSO, you can order hardcover and paperback from Barnes & Noble. In addition, our own publishing house offers these bookstore links to order hardcovers as well as paperbacks directly from our supplier.

.