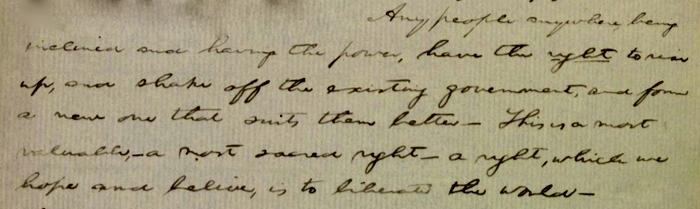

Click on this brief passage from Lincoln’s 1848 speech in the U.S. House about the War with Mexico to see the entire manuscript at the Library of Congress website. This passage appears on page 25 of Lincoln’s hand-written text for his speech.

.

By DUNCAN NEWCOMER

Host of the ‘Quiet Fire’ series

This is Quiet Fire, a meditation on the spiritual life of Abraham Lincoln and its relevance to us today. Welcome.

Here’s a Lincoln quote for you:

“Any people anywhere, being inclined and having the power, have the right to rise up, shake off the existing government, and form a new one that suits them better. This is a valuable—a most sacred right—a right, which we hope and believe, is to liberate the world.”

Lincoln echoes Thomas Jefferson’s declaration of the right to revolution and Jefferson’s later call to on-going revolutions. Natural Law was, to Jefferson, reason enough for such a human right. Lincoln, who could choose words as carefully as Jefferson, calls it a sacred right.

Can there be sacred politics?

The quote is from a speech Lincoln delivered in 1848 to the U.S. House of Representatives. Europe was aflame with revolutions—especially France and Hungary. Lincoln was serving is in his one term in Congress.

His thinking is both global—and limited. In this speech, when Lincoln calls for the sacred right of revolution he is thinking of white men, not black slaves, and he is not thinking about Southern secession in the U.S. This is a limited and secular political speech, given potency by the word “sacred.”

Laslo Kossuth

Soon the U.S. Congress would be addressed by the traveling Lajos Kossuth, famous leader of the Hungarian Revolution of 1848. Lincoln sponsored a celebration for Kossuth in Springfield in 1851. Kossuth gave a speech in Ohio in 1852 saying, “The spirit of our age is Democracy. All for the people, and all by the people. Nothing about the people without the people.”

Lincoln would have liked that, no?

Later Lincoln would wear a Kossuth-style hat in his disguise when he clandestinely snuck into Washington as President Elect, avoiding assassination plots. Kossuth, somewhat like Lincoln, learned English by reading Shakespeare, and was said to be the greatest orator of his day.

But why would Lincoln use the word sacred in this 1848 speech on revolution? Is this stained-glass window dressing?

We, who are pursing here the spiritual life of Lincoln in this Quiet Fire series, need to know what is sacred about a seemingly secular political speech by Lincoln.

Religions tell us that the Sacred is something beyond the here and now, the place and time of our lives. It is something universal and eternal. Those are the truth claims of the sacred, and here Lincoln is making a universal claim saying, “any peoples anywhere” have this right to revolution. His belief that there is something sacred about his secular point of view is a built-in multiplier.

Lincoln scholar John Burt has praised Lincoln’s mind and spirit for the implications embedded in his values. These unfolding implications are the hallmark of spiritual values. It is why they lead to both transformation and tragedy. There exists within values “a penumbra of implications that stretch off into shadow.” Burt concluded in his book, Lincoln’s Tragic Pragmatism.

In this Quiet Fire series, we have called it Lincoln’s Yonder vision and it leads through the valley of the shadow of death. Such values reach beyond the here, reach everywhere, and beyond the now, into the eternal. They involve us in the will of God, greater than the will of any one people or person. That is, in part, the irony of American history. More is going on than we know or even think.

The poet Robert Penn Warren once said that evil is what happens on the way to doing good. Sacred values take us beyond our secular capacities to bring them to life. We are only partial beings and we create evil—like civil war—on the way to creating something good—like union and freedom.

High ideals have high costs, partly because when something is trans-human it can also easily become inhuman. “But we only know the meaning of political ideas once we have lived our way into them” adds John Burt.

Who could have dreamed that Jefferson’s ideas of equality would be re-proclaimed by Lincoln, then re-spoken by Elizabeth Cady Stanton, then Martin Luther King, Jr., and then in the spirit of LGBTQ rights? But we have lived that and are living more.

Sacred doesn’t just make something beautiful, real or good. It makes something apocalyptic and God-given, transformative.

This is how the spiritual life of Lincoln is beyond the national life of America. Lincoln has this Yonder vision of human equality, the precious quality of people as people.

Lincoln could not prove that this right to “revolutionize” was sacred. But Jefferson couldn’t prove that revolution and equality were from Natural Law either. He would use the idea of natural law to express his ideas about a natural law. We use sacred imagination to express the meaning of Lincoln’s idea of sacred rights in secular history.

Sacred imagination is what we get when we combine intuition, common sense, and a good dash of psychology and theology. This is our task now, to find the eternal in the temporal, and the universal in the useful, just as Lincoln did.

Values, such as equality, contain within them unpredictable consequences. Only by living them, in the action and passion of our time, does more light shine from those values and more implications come out of the shadows.

Our moral investment in each other becomes a consequence of this sacred point of view. We don’t know what further good might unfold in the midst of action and reaction, on both sides.

When we celebrate the values in Lincoln’s spiritual life we tend not to calibrate the consequences of his murder. But certainly in his life most things just didn’t work out as planned. They worked out over time and sometimes they didn’t work out at all. Life with a Living God, his last term for God, is simply a work in progress. Tragic conflicts and consequences happen. Freedom is still being defined today, in the life of a living God and in the spiritual life of those who care.

In the spiritual life of Lincoln the most important words Lincoln ever uttered were these three, “a Living God.”

As far as I know he only uses these words a few times. Once was when he repeats them after Dr. Gurley his Presbyterian minister uses them in sharing the Gospel news with Lincoln that his dead son Willie is with the Living God.

To Lincoln this means, that like Lincoln himself, Willie is still within the realm of life because God is a living God. Lincoln applies theologically what he learned logically from Euclid: if one thing is equal to another thing, that is itself equal to a third thing, then that first thing is also equal to it.

If Willie is with the Living God, and God is a living God, then as I live with a Living God, I also live with Willie.

But even more, it is a Living God that Lincoln reveals in his Second Inaugural. Such a Living God is in the events of this history. Lincoln comes to the Biblical place: God is a Living God and we are judged and then are tasked with mercy, charity, for a rebirth of justice, freedom and peace with all nations.

The spiritual life of Lincoln takes him through the tragic consequences of sacred values, and such a spiritual life can take us to the threshold of rebirth.

This is Duncan Newcomer and this has been Quiet Fire, the spiritual life of Abraham Lincoln.

.

Care to Enjoy More Lincoln Right Now?

GET A COPY of Duncan’s 30 Days with Abraham Lincoln—Quiet Fire.

Each of the 30 stories in this book includes a link to listen to the original radio broadcasts. The book is available from Amazon in hardcover, paperback and Kindle versions. ALSO, you can order hardcover and paperback from Barnes & Noble. In addition, our own publishing house offers these bookstore links to order hardcovers as well as paperbacks directly from our supplier.

.

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 4: The courage to say—’In spite of all this, I will be!’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 1: In this cruel month of death, what will be our legacy?

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 2: Coping with the Uncertainty and Mystery of a Deadly Disease

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 3: We Must Rise with the Occasion

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln: When will we be good? God knows!

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 6: Lincoln’s Courage to Judge and to Lament

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 7: Lincoln looks toward his spiritual hero, Washington

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 8: Four Score and Seven

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 9: A Unique Spiritual Quest and The Pilgrim’s Progress

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 10—When all three meet: Lincoln, black people and the Bible.

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 11—Raising a Flag and Contemplating the Sacred Pillars of America

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 12—Why do we refer to our most eloquent president as ‘Quiet’?

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 13—Ultimately, we are responsible for our faces.

- In Our Struggle for Freedom, the Truth is Not in Our Statues—It’s in Our Souls

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 16—In racial justice, ‘We … bear the responsibility.’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 17—Remembering Mrs. Keckley, a close friend who Lincoln realized he did not truly know

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln: Remember when a president’s 1st value was Kindness?

- Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 19—’The election was a necessity’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 20—’A Most Sacred Right’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 21—Locating the spiritual X-factor in Lincoln’s ground-breaking life

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 22—Lincoln shows us the power of holding even opposites together

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 23—The forest vision Lincoln shared with poet Rabindranath Tagore

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 24—Myths and wisdom in national conversation about rule of law

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 25—How a true leader expresses the nation’s grief

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 26—Choosing Humility over Humiliation

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 27—What shaped Lincoln’s soul?

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—Here’s to you Mrs. Robinson!

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—Now, we’re all hoping for ‘Yonder’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—In three words, he said it: ‘We are elected.’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—Let’s remember how he reached across the aisle to discover new friends

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—Marking the anniversary of those 272 words at Gettysburg

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—’The Last Best Hope of Earth’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—’A Christmas Carol’ with Abraham Lincoln