�Shapell Manuscript Foundation. All Rights Reserved. For more information, please contact us at www.shapell.org.

EDITOR’s NOTE—September 2020 has been marked by many tragedies nationwide—from wildfires in the West to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic to reflections on the 19th anniversary of the terrorist attacks on 9/11/2001. Our national conversation has often turned to the best examples of leadership in times of tragedy—so, Lincoln scholar Duncan Newcomer reminds us of this famous presidential response in 1862.

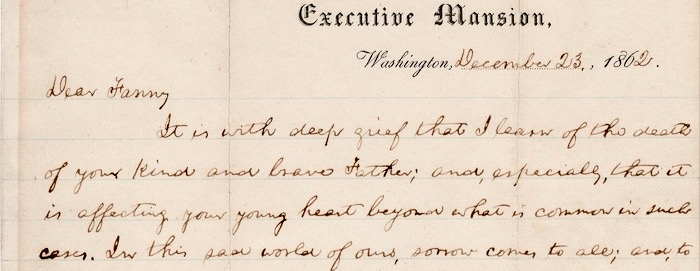

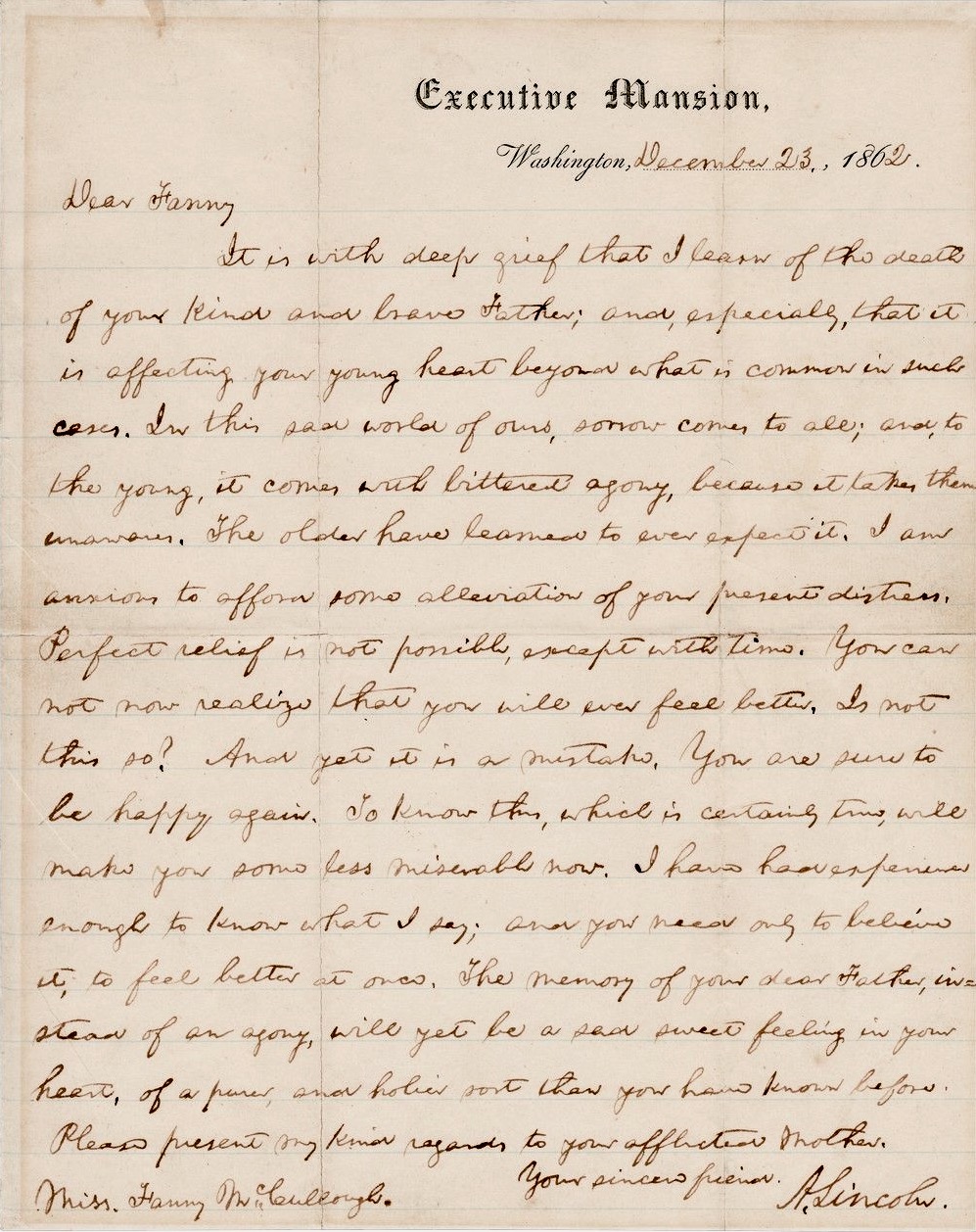

CLICK ON THIS snapshot of the 1862 letter to see it enlarged on your screen. (Shapell Manuscript Foundation. All Rights Reserved. For more information, contact us at www.shapell.org.)

By DUNCAN NEWCOMER

Host of the ‘Quiet Fire’ series

This is Quiet Fire, a reflection on the spiritual life of Abraham Lincoln and its relevance to us today. Welcome.

Here’s a Lincoln quote for you, which I’ve condensed for you: “In this sad world of ours, sorrow comes to all.”

This is care and wisdom from the ready quill of Abraham Lincoln. It is in a personal letter to a young woman back in Illinois, Fanny McCullough, whose father was just killed in a Civil War battle in Mississippi.

In the spiritual life of Lincoln his ability to care is extraordinary.

To the historian who wrote Team of Rivals, Doris Kearns Goodwin, such letters reveal “what may have been the most important of his emotional strengths—his unusual empathy, his gift of putting himself in the place of others…”

Lincoln’s letters of compassion come from a space in his heart that opens into a space in the receiver’s heart.

Not only are his words unbounded by space they are also timeless.

Fanny, in Illinois, will know his care, and eventually in our time we can also. Such feelings are mystical but they are also ethical.

Lincoln felt personally responsible for this man’s death and his daughter’s grief. He knew her father—a local sheriff and county clerk. He was an older man, had a crippled arm and was partially blind. He implored Lincoln to let him fight for America, fight for the union and the democracy that it was achieving. And so he had become Lt. Col. William McCullough. Killed on December 6th, 1862, 157 years ago, leaving behind his daughter and her mother.

Lincoln’s expressed empathy crosses space and time. But when you read it you don’t feel that this was written so long ago, December 23rd, two days before Christmas, 1862.

Lincoln writes to Fanny that time itself will help her heal. He says that her agony will change, over time, into “a sad sweet feeling in your heart, of a purer, and holier sort than you have known before.”

So this will be a revelation to her, a new and unknown place that he asserts as pure and holy. Is this not the spiritual life of Lincoln being created then and even shared now?

All scriptures are replete with stories and myths of space and time being crisscrossed by something spiritual.

But Lincoln of course, like all of us, was embedded in secular time. Let us look. It is December 23rd, 1862, and in ten days the final proclaiming of the Emancipation Proclamation will take effect. Ten days before Lincoln wrote this letter the Union army suffered 12,000 casualties in an horrific defeat at Fredericksburg. How could Lincoln have on his mind and heart 12,000 men lost, and then also one man lost, and one daughter in agony, and then, by his words alone, millions of slaves behind Confederate lines suddenly legally free. To add to the weight of time, for Lincoln, it has been just ten months since his dearest son Willie died.

In such a heavy time Lincoln asserts this loving wisdom, “I am,” he writes, “anxious to afford some alleviation to your present distress. Perfect relief is not possible, except with time. You cannot now realize that you will ever feel better. Is not this so? And yet it is a mistake. You are sure to be happy again. To know this, which is certainly true, will make you some less miserable now. I have had experience enough to know what I say; and you need only to believe it, to feel better at once.”

This is age-old wisdom, his pragmatic faith. “You need only to believe it to feel better at once,” he says.

This of course is an assertion of the spiritual principles promoted by many other American sages, including Phineas Quimby and Mary Baker Eddy: that divine love coupled with thinking can make something so.

In these dimensions beyond space and time Lincoln’s spiritual life can light us down in honor and in love even to the latest generation.

This is Duncan Newcomer, and this has been Quiet Fire. The spiritual life of Abraham Lincoln.

.

.

.

Care to Enjoy More Lincoln Right Now?

Care to Enjoy More Lincoln Right Now?

GET A COPY of Duncan’s 30 Days with Abraham Lincoln—Quiet Fire.

Each of the 30 stories in this book includes a link to listen to the original radio broadcasts. The book is available from Amazon in hardcover, paperback and Kindle versions. ALSO, you can order hardcover and paperback from Barnes & Noble. In addition, our own publishing house offers these bookstore links to order hardcovers as well as paperbacks directly from our supplier.

.

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 4: The courage to say—’In spite of all this, I will be!’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 1: In this cruel month of death, what will be our legacy?

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 2: Coping with the Uncertainty and Mystery of a Deadly Disease

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 3: We Must Rise with the Occasion

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln: When will we be good? God knows!

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 6: Lincoln’s Courage to Judge and to Lament

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 7: Lincoln looks toward his spiritual hero, Washington

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 8: Four Score and Seven

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 9: A Unique Spiritual Quest and The Pilgrim’s Progress

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 10—When all three meet: Lincoln, black people and the Bible.

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 11—Raising a Flag and Contemplating the Sacred Pillars of America

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 12—Why do we refer to our most eloquent president as ‘Quiet’?

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 13—Ultimately, we are responsible for our faces.

- In Our Struggle for Freedom, the Truth is Not in Our Statues—It’s in Our Souls

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 16—In racial justice, ‘We … bear the responsibility.’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 17—Remembering Mrs. Keckley, a close friend who Lincoln realized he did not truly know

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln: Remember when a president’s 1st value was Kindness?

- Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 19—’The election was a necessity’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 20—’A Most Sacred Right’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 21—Locating the spiritual X-factor in Lincoln’s ground-breaking life

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 22—Lincoln shows us the power of holding even opposites together

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 23—The forest vision Lincoln shared with poet Rabindranath Tagore

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 24—Myths and wisdom in national conversation about rule of law

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 25—How a true leader expresses the nation’s grief

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 26—Choosing Humility over Humiliation

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 27—What shaped Lincoln’s soul?

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—Here’s to you Mrs. Robinson!

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—Now, we’re all hoping for ‘Yonder’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—In three words, he said it: ‘We are elected.’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—Let’s remember how he reached across the aisle to discover new friends

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—Marking the anniversary of those 272 words at Gettysburg

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—’The Last Best Hope of Earth’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—’A Christmas Carol’ with Abraham Lincoln