FANCIFUL AND FUN—BUT NOT FACTUAL—This was a popular lithograph envisioning Lincoln leaving Springfield for his long journey to Washington D.C. It’s a cheery image pro-Lincoln families could hang on the wall. But—it’s not how that scene actually unfolded. (Below, today, we have a journalist’s eye view.)

.

By DUNCAN NEWCOMER

Host of the ‘Quiet Fire’ series

This is Quiet Fire, a meditation on the spiritual life of Abraham Lincoln and its relevance to us today. Welcome. Here’s a Lincoln quote for you:

“Friends—No one, not in my situation, can appreciate my feeling of sadness at this parting.”

These are the first words of Lincoln’s Farewell Address, given on a rainy morning, February 11, 1861, at the railroad depot in Springfield. A thousand or so of his friends and neighbors, no doubt some barking dogs as well, are up early to bid him fare well as he leaves home to become President.

It is called an address. It is shorter than the Gettysburg Address. Very uncharacteristically, Lincoln spoke without notes. His words are prayer-like and they invoke the mystic chords of memory and the abiding presence of the Divine Being who can be “everywhere for good”.

The words of his Address are so prayer-like that you can sense the silence within them and the silences that must have fallen upon the upturned faces listening to him.

The heart-felt sincerity of his words that day are obvious in the way he delivered them—spontaneously, without having written down any script in advance, not even notes.

HENRY VILLARD about the time he covered Lincoln’s rise to the presidency. (Click his photo to read his Wikipedia biography.)

However, once he spoke them, his parting words were so poignant that Associated Press correspondent Henry Villard begged him to commit the words to paper. So, as the train jolted along the tracks, Lincoln and his secretary did just that, which is why we have them today.

Had Villard not insisted, Lincoln would have left the station, the words only held in the memories of the crowd, and would have returned to his more characteristic silence.

Silence follows Lincoln like a spiritual friend wherever he goes. Sandburg has written that the element of silence was great in the making of this man. Many of the personal reminiscences written by the men and the women of his time will say that conversation with Lincoln began with his extended and silent listening to them.

This, then, is the “quiet” that is in the quiet fire of Abraham Lincoln.

Now one reason so many people, for so many years, have found, and are finding, something about Lincoln they love is that he was a many-sided person. There is hardly a characteristic of Lincoln for which he did not also possess the opposite. He had many paradoxes, a Euclidian array of equal opposites. And they all held together. He didn’t just hold the county together, he kept his head together. It wasn’t just 36 states he eventually held in union.

People find a side of Lincoln they love: his logic, his heart, his humor, his sorrow, his power, his humility, his voice, his written words, AND his unspoken inside side.

This is reason we can talk about the spiritual life of Lincoln. He was extraordinarily deep, inside. His was a well spring.

There is as much fire in Lincoln as there is quiet. His fire gives off light, heat, inspiration and power. His quiet contains a sense of yonder, his intelligence, and his well spring of goodness.

We have a language for these paradoxes in Lincoln. We can talk about introverts and extraverts. In his own paradoxical way Lincoln was defiantly both. You can feel the introversion in his Farewell Address. “My Friends, No one, not in my situation, can appreciate my feelings of sadness at this parting.”

This is as close as we ever get to Lincoln saying out loud, “You just don’t know how I feel.”

His law partner Billy Herndon once said that he felt he never really knew Lincoln, that no one did, that Lincoln held himself close to his own chest in a quiet almost mysterious way.

Of course in this Farewell Address Lincoln is sharing his inner life. And they do know how he feels because he is addressing their inner life too. In fact, emotionally, every one there is in his situation as well—they are the other side of this painful parting. He is addressing the unspoken feelings that everyone is feeling, feeling inside. He is giving voice to what they all are feeling.

But no one else was in his situation, no one else is going off to be President. The only such company Lincoln can feel would be the silent presence of George Washington, whom he mentions and who was also once going off to be President of a new nation in crisis.

Silence is how the spirit is present, in joy and in sorrow, in terror and in beauty, in deep feelings and in long thoughts. It is the way we feel awe and horror.

Silence is how we start and end prayer. Silence is how we feel before we applaud the uplift of a symphony, or how we feel unspeakable joy at the emerging site of a new born child. Silence is what we feel when we have sighs too deep for words, or gasp at some unspeakable wrong.

This is the range of silence that Lincoln brought with him from the wilderness to Washington.

We can love the inside story of this man, noting, as maybe a few did on that rainy morning, that it was February 11th and the next day their gawky neighbor would have his birthday, his fifty-second. He would have celebrated many birthdays in Springfield. But this often tightlipped man makes no mention of that in his farewell.

This is a bit of the quiet that is part of the paradox of Lincoln’s quiet fire, and it can follow us down in honor to the latest generation.

This is Duncan Newcomer and this has been Quiet Fire, the spiritual life of Abraham Lincoln.

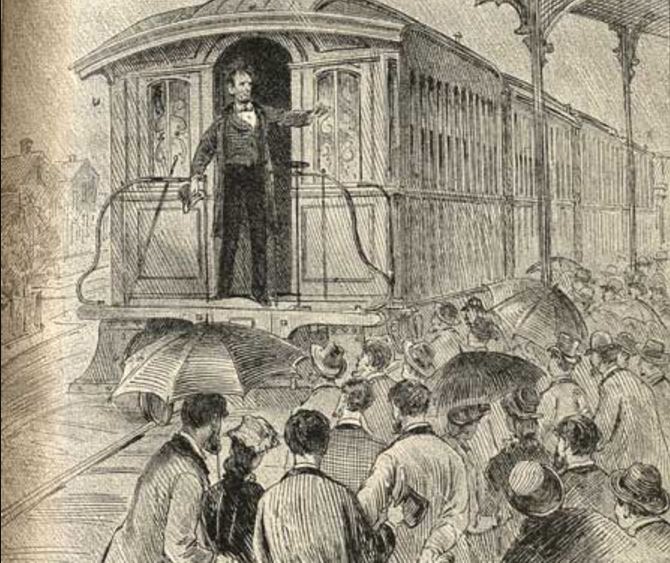

And this is what the day actually looked like, thanks to a journalist’s sketch—

.

.

Care to Enjoy More Lincoln Right Now?

GET A COPY of Duncan’s 30 Days with Abraham Lincoln—Quiet Fire.

Each of the 30 stories in this book includes a link to listen to the original radio broadcasts. The book is available from Amazon in hardcover, paperback and Kindle versions. ALSO, you can order hardcover and paperback from Barnes & Noble. In addition, our own publishing house offers these bookstore links to order hardcovers as well as paperbacks directly from our supplier.

.

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 4: The courage to say—’In spite of all this, I will be!’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 1: In this cruel month of death, what will be our legacy?

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 2: Coping with the Uncertainty and Mystery of a Deadly Disease

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 3: We Must Rise with the Occasion

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln: When will we be good? God knows!

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 6: Lincoln’s Courage to Judge and to Lament

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 7: Lincoln looks toward his spiritual hero, Washington

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 8: Four Score and Seven

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 9: A Unique Spiritual Quest and The Pilgrim’s Progress

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 10—When all three meet: Lincoln, black people and the Bible.

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 11—Raising a Flag and Contemplating the Sacred Pillars of America

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 12—Why do we refer to our most eloquent president as ‘Quiet’?

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 13—Ultimately, we are responsible for our faces.

- In Our Struggle for Freedom, the Truth is Not in Our Statues—It’s in Our Souls

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 16—In racial justice, ‘We … bear the responsibility.’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 17—Remembering Mrs. Keckley, a close friend who Lincoln realized he did not truly know

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln: Remember when a president’s 1st value was Kindness?

- Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 19—’The election was a necessity’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 20—’A Most Sacred Right’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 21—Locating the spiritual X-factor in Lincoln’s ground-breaking life

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 22—Lincoln shows us the power of holding even opposites together

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 23—The forest vision Lincoln shared with poet Rabindranath Tagore

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 24—Myths and wisdom in national conversation about rule of law

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 25—How a true leader expresses the nation’s grief

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 26—Choosing Humility over Humiliation

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 27—What shaped Lincoln’s soul?

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—Here’s to you Mrs. Robinson!

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—Now, we’re all hoping for ‘Yonder’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—In three words, he said it: ‘We are elected.’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—Let’s remember how he reached across the aisle to discover new friends

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—Marking the anniversary of those 272 words at Gettysburg

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—’The Last Best Hope of Earth’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—’A Christmas Carol’ with Abraham Lincoln