By DUNCAN NEWCOMER

Host of the ‘Quiet Fire’ series

This is Quiet Fire, a meditation on the spiritual life of Abraham Lincoln and its relevance to us today. Welcome. Here’s a Lincoln quote for you:

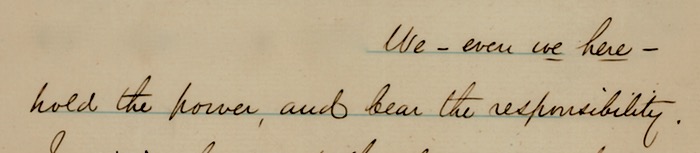

“We—even we here—hold the power, and bear the responsibility. In giving freedom to the slave, we assure freedom to the free—honorable alike in what we give, and in what we preserve.”

In other words, Lincoln would agree with James Baldwin and the powerful voices in our time who say that America’s racial injustices are not the responsibility of Black Americans to fix. White Americans must address systemic injustice built by White Americans.

This week’s quote comes from Lincoln’s message to Congress on December 1, 1862. This lengthy address came in the midst of Lincoln’s eroding political support. His Republicans had lost seats in five populous Northern states. He had announced that the Emancipation Proclamation would go into effect on the first day of 1863. The war would now be about freeing slaves as much as saving the Union.

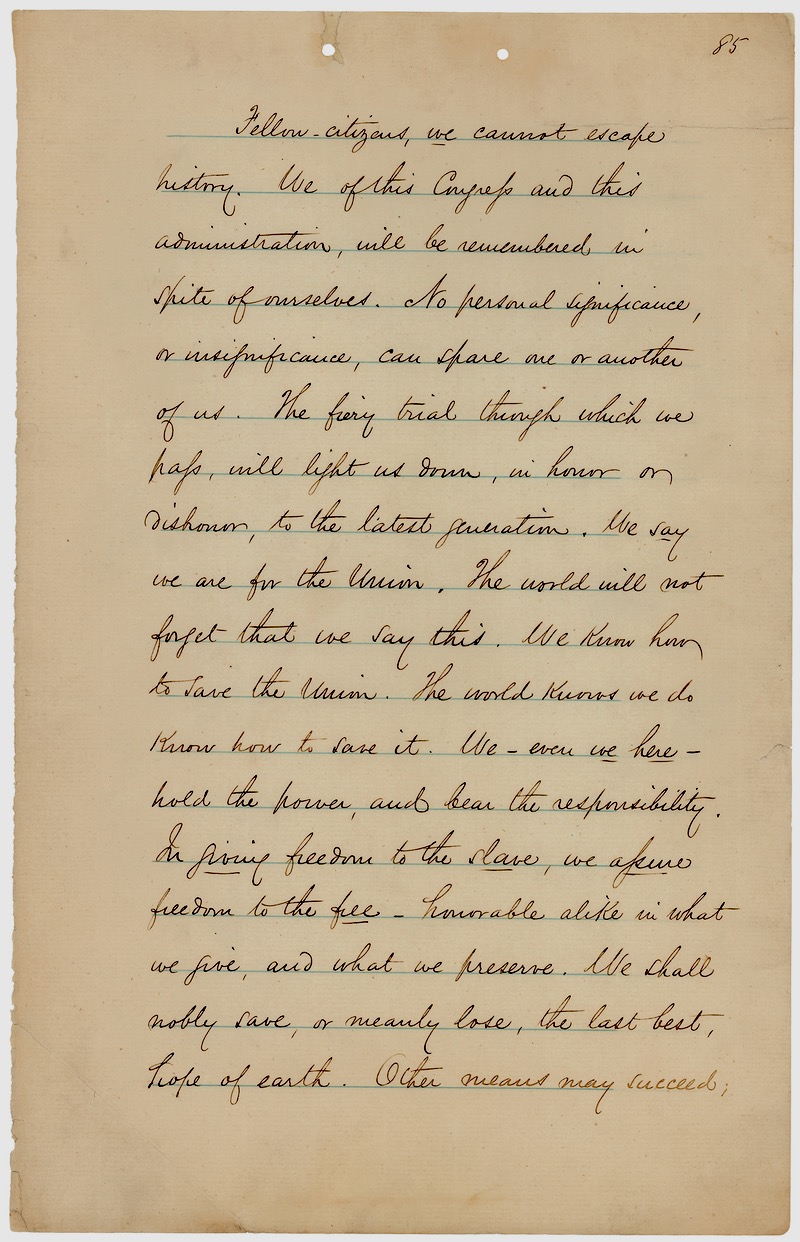

So, he addressed Congress with a long and elaborate argument in support of emancipation for the good of the war effort, the good of the country and the good of humanity. His message that day was 8,400 words. His hand-written text of it ran across 86 pages of stationery!

(EDITOR’s NOTE—You can see page 85, which accompanies this column below, by clicking on the image to enlarge it. Or, you can see more of the context surrounding the brief, highlighted quote today by reading the text at the bottom of this column. If you want to wade into the whole address, here is a complete transcript of the message.)

As Lincoln reaches the conclusion of his long address, he is winsome and dramatic.

As Lincoln reaches the conclusion of his long address, he is winsome and dramatic.

He begins with the word “We” and then punctuates his text with dashes and underlining to ensure that he stresses: even we here! He wants his audience to clearly understand that his call to action is aimed directly at these men sitting in Congress.

Lincoln is emphasizing that moral agency belongs to those who hold the power. “We—even we here—hold the power and bear the responsibility.”

“We”—the White men in Congress at that moment and, if we truly are listening to Lincoln, White Americans today—bear this responsibility, not because we are good, but because we are the responsible party. We created this mess and we are supposed to fix it.

But that is only half of the remarkable spiritual wisdom of Lincoln here. The other half is what we, the Whites, are going to get out of this effort. Lincoln declares that in giving freedom—we assure our own freedom. We preserve freedom as our shared value.

At that moment, Lincoln is telling White power brokers that they are going to receive the very thing they are also giving away: freedom.

Lincoln knows that his White world will never be free, will never have the assurance of freedom, as long as Black people are enslaved. A nation cannot hold its democratic values together through violence, oppression, cruelty and injustice.

A system wherein a privileged class eats the bread from the sweat of another’s labors can never maintain itself without violence. And, Lincoln says, violence is ultimately destructive of two things: honor and democracy.

Honor. Lincoln frames this whole argument around the word honor. What is honor but the ability to trust the goodness of oneself and each other? In Lincoln’s language, trust based on honor is what democracy itself requires. There must be a basic minimum of individual trust, goodness. Law and order require equality and justice, Lincoln knows.

So he is pragmatic and also spiritual. We see that as he describes giving what we receive, and at that time freedom was something to give. Nowadays, however, the issue is equality and justice. The question we all face today is: Who holds the power to correct the systems of inequality that have crippled America in the 158 years since slavery officially ended? Who, now, is responsible for addressing those toxic systems? We must assume, as Lincoln did, that it is most assuredly the White institutions and the mentality of the people who run them that hold the power and bear the responsibility.

That was also the challenge laid down by James Baldwin who said: You are the problem. Don’t try to make it about me. He wrote, “I am not your Negro.”

To Lincoln equality is to be assumed. Equality must be in the air, an assumption as much as a fact. We must come to a point where all Americans truly share in this truth. Lincoln’s assumption follows the same spiritual logic that we heard from Martin Luther King when he preached that the purpose of non-violent resistance was two-fold: It called forth a wrong as it demanded it be righted—and, it named the White person’s evil. It made the White person see and feel just who he or she had become. That untwisting of a moral distortion was the gift that Black non-violent action so painfully gave to the rest of us.

This is what makes Lincoln a spiritual leader as much as a political leader. He felt deep down that the system of Black slavery held him—and the nation—in bondage to a tragically and morally flawed system. If he could let slaves go free—he could free the nation of captivity from this self-inflicted evil.

So, today, we are in a different chapter of American history. Our flawed systems of racial injustice have different shapes, although they are as deeply entwined in the structure of our nation than they ever were. Restoring our proclaimed American values will be nearly as traumatic today as it was in Lincoln’s era. And that is why we keep turning to Lincoln for spiritual wisdom in facing such complex moral, spiritual and systemic challenges.

We are no longer debating emancipation as Congress was in 1862. No one suggests that Lincoln’s specific policies should guide us in our era. He kept changing them himself to adapt as events around him changed. Not even Lincoln himself wound up adopting the convoluted emancipation proposal he included in that 1862 message to Congress. Lincoln is not on the ballot today, nor should he be. What millions of Americans are protesting, today, are entirely different forms of these bars and chains that are the legacy of slavery.

The reason millions of Americans still look to Lincoln as “the soul of America” is because of the spirit that guided him—that opened up such a compelling vision of America’s purpose and potential. And, today, the timely truth Lincoln calls us to remember is our responsibility to act.

The recognition of the equality of another human being is a timeless, spiritual truth. The recognition of our responsibility to assure that freedom is a spiritual calling. As Lincoln said in this same 1862 address to Congress: We must shed the myths and biases and injustices of the past. His words were: “The dogmas of the quiet past are inadequate to the stormy present.” That line that could be uttered in our streets today.

We must wake up to the realities we face, Lincoln said. “We must disenthrall ourselves, and then we shall save our country.”

And, if our heads and hearts do clear—then, we shall begin to glimpse the tasks ahead of us. For White Americans, it is the power and responsibility for correcting injustice—because, even in our day, “we—even we here—hold the power and bear the responsibility.”

This is Duncan Newcomer, and this has been Quiet Fire, the spiritual life of Abraham Lincoln.

.

Care for More Context?

In understanding our brief passage from page 85 of Lincoln’s hand-written text, it may help to read a bit more from this concluding portion of his message:

“The dogmas of the quiet past are inadequate to the stormy present. The occasion is piled high with difficulty, and we must rise with the occasion. As our case is new, so we must think anew and act anew. We must disenthrall ourselves, and then we shall save our country.

“Fellow-citizens, we can not escape history. We of this Congress and this Administration will be remembered in spite of ourselves. No personal significance or insignificance can spare one or another of us. The fiery trial through which we pass will light us down in honor or dishonor to the latest generation.

“We say we are for the Union. The world will not forget that we say this. We know how to save the Union. The world knows we do know how to save it.

“We—even we here—hold the power and bear the responsibility. In giving freedom to the slave we assure freedom to the free—honorable alike in what we give and what we preserve. We shall nobly save or meanly lose the last best hope of earth. Other means may succeed; this could not fail.

“The way is plain, peaceful, generous, just—a way which if followed the world will forever applaud and God must forever bless.”

.

.

Care to Enjoy More Lincoln Right Now?

GET A COPY of Duncan’s 30 Days with Abraham Lincoln—Quiet Fire.

Each of the 30 stories in this book includes a link to listen to the original radio broadcasts. The book is available from Amazon in hardcover, paperback and Kindle versions. ALSO, you can order hardcover and paperback from Barnes & Noble. In addition, our own publishing house offers these bookstore links to order hardcovers as well as paperbacks directly from our supplier.

.

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 4: The courage to say—’In spite of all this, I will be!’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 1: In this cruel month of death, what will be our legacy?

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 2: Coping with the Uncertainty and Mystery of a Deadly Disease

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 3: We Must Rise with the Occasion

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln: When will we be good? God knows!

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 6: Lincoln’s Courage to Judge and to Lament

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 7: Lincoln looks toward his spiritual hero, Washington

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 8: Four Score and Seven

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 9: A Unique Spiritual Quest and The Pilgrim’s Progress

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 10—When all three meet: Lincoln, black people and the Bible.

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 11—Raising a Flag and Contemplating the Sacred Pillars of America

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 12—Why do we refer to our most eloquent president as ‘Quiet’?

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 13—Ultimately, we are responsible for our faces.

- In Our Struggle for Freedom, the Truth is Not in Our Statues—It’s in Our Souls

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 16—In racial justice, ‘We … bear the responsibility.’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 17—Remembering Mrs. Keckley, a close friend who Lincoln realized he did not truly know

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln: Remember when a president’s 1st value was Kindness?

- Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 19—’The election was a necessity’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 20—’A Most Sacred Right’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 21—Locating the spiritual X-factor in Lincoln’s ground-breaking life

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 22—Lincoln shows us the power of holding even opposites together

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 23—The forest vision Lincoln shared with poet Rabindranath Tagore

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 24—Myths and wisdom in national conversation about rule of law

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 25—How a true leader expresses the nation’s grief

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 26—Choosing Humility over Humiliation

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 27—What shaped Lincoln’s soul?

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—Here’s to you Mrs. Robinson!

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—Now, we’re all hoping for ‘Yonder’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—In three words, he said it: ‘We are elected.’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—Let’s remember how he reached across the aisle to discover new friends

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—Marking the anniversary of those 272 words at Gettysburg

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—’The Last Best Hope of Earth’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—’A Christmas Carol’ with Abraham Lincoln