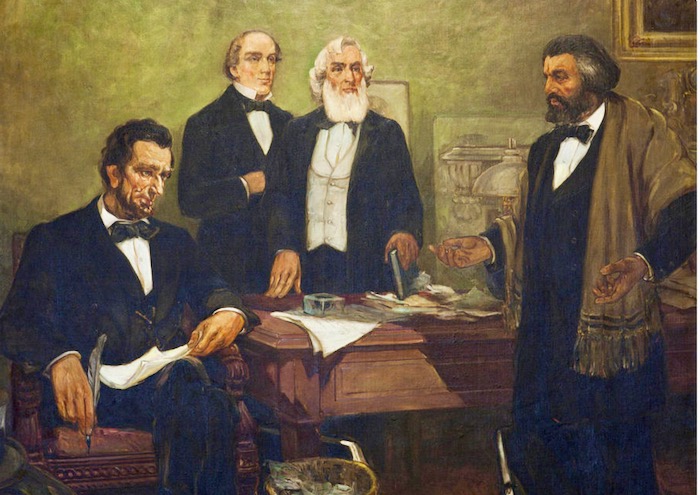

TWO HISTORICAL MILESTONES IN A SINGLE IMAGE: Frederick Douglass met Lincoln face to face three times. This famous painting depicts his first appeal to Lincoln in 1862 to combat discrimination in the Union army against black soldiers. The main effort to recruit black regiments began only after the Emancipation Proclamation took effect in January 1863. No photographs were taken during that meeting. This 1943 painting of the encounter is a milestone for two reasons. First, it broke new ground because it was an official U.S. government commission painted for public display by an African-American artist, William Edouard Scott. Second, it depicted Douglass in a clearly dominant position as he argued the case of black troops with a seated and weary Lincoln.

.

By DUNCAN NEWCOMER

Host of the ‘Quiet Fire’ series

This is Quiet Fire, a reflection on the spiritual life of Abraham Lincoln and its relevance to us today. Welcome.

Nestled into many Lincoln literary collections, there is a large red book, Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln by Distinguished Men of His Time, published in 1885 by Allen Thorndike Rice, editor of the famous North American Review. My copy of Rice’s classic is in the autumn-leaves season of its life.

Included in these pages are the memories of 33 men, none more interesting than that of Frederick Douglass, interesting and representative of Lincoln’s silent empathy as he greeted him into his office.

Douglass, the famous Black abolitionist and feminist was an awe-inspiring man in his own right. After his encounter with Lincoln, he wrote, “I was somewhat troubled with the thought of meeting one so august and high in authority….but my embarrassment soon vanished when I met the face of Mr. Lincoln. When I entered he was seated in a low chair, surrounded by a multitude of books and papers, his feet and legs were extended in front of his chair. On my approach he slowly drew his feet in from the different parts of the room into which they had strayed, and he began to rise, and continued to rise until he looked down upon me, and extended his hand and gave me a welcome…. ‘You need not tell me who you are Mr. Douglass, I know who you are. Mr. Sewell has told me all about you.’ He then invited me to take a seat beside him.”

After Douglass presented his four points, which had to do with the recruitment, the pay, the safety and the honor of what they both called “the colored troops,” Douglass writes, “To this little speech Mr. Lincoln listened with earnest attention and with a very apparent sympathy….”

Again and again, Lincoln’s earnest and silent opening attention is what these men record. It puts them at ease, it honors their mission, and it enhances their dignity.

This book collects memories of famous men like U.S. Grant and Henry Ward Beecher, and less famous men like Schuyler Colfax and Elihu Washburn, who tell the of same welcoming encounter.

It is easy to see Lincoln unscrambling his long legs, striding toward the guest, his huge hand extended, his voice rising in greeting, and then his quiet attentive listening. Lincoln begins these meeting again and again with silence.

The hallmark of such a greeting is spiritual. The moment begins dwelling in silence, and it is physical. It is embodied. It communicates dignity and respect.

This is not the politics of humiliation, as recently critiqued in a New York Times editorial by Thomas L. Friedman on September 8, 2020.

This is the politics of humility.

It is both smart and good on Lincoln’s part. Smart because, as he once said, if you are to convince a man of your opinion you must first persuade him that you are his sincere friend. It is good because it places the esteem, the sense of the self-worth of the visitor, at the center of the conversation.

Lincoln loved to meet people. Quite simply, love was in his heart. One day while he was a young boy, he ran up to the split-rail fence to greet a visitor who had just ridden up. Lincoln began talking excitedly with the man. His father, Thomas Lincoln, struck his son down with his hand. Lincoln’s offense had been to speak first, before his father. However, as young Lincoln’s life unfolded, he preserved his natural affinity for people.

One of Lincoln’s favorite books was John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress. In that book, a sinful character is appropriately named Talkative. Lincoln must have liked that sinner, because he certainly knew how to be talkative. But Lincoln also had a humble spirit, and he knew how to respect others.

It is really hard to humiliate someone who is humble. They just don’t go down.

Now Lincoln himself was the object and target of political satire and even craven contempt. What we don’t ever see in Lincoln is pay-back. He once said, “What I have to deal with is too vast for malice.”

So he holds a penetrating and deep silence when he meets a fellow human being. He expands his heart and furthers his mind reaching for human value, knowledge, and things too vast for malice.

Contempt, the inner looking down on someone, is a secular human behavior that all religions and spiritual practices counter. Loving your neighbor as yourself is a universal law of spiritual life. And it is very hard to come by.

George Washington, while desperately trying to defend the city of New York against the invading British fleet, was given needed reinforcements from New England, especially a group from Vermont called the Green Mountain Boys.

Washington was a Virginia gentleman, the wealthiest man in the state. He was well-practiced in proper rank and file behavior, in proper uniforms, and speech and discipline. When, earlier, he was in the British Colonial army he himself was openly humiliated by the English as a rube Colonial. He had a lot of pride and so quit out of a sense of his own honor.

But when he encountered the New England mountain boys as his new recruits he was nothing but disgusted with the rowdy Vermonters. He wrote home of his utter contempt for them. A spirit of humility is hard-earned.

A few generations later these tables turn in a story of the New York governor and future presidential candidate William Seward. He and his wife decided to tour the South in the years before the war.

The Sewards were contemptuous of the whole southern way of life. Not only were they disgusted with slavery, but they were revolted by the pomposities of plantation manners, the lack of general education, the run-down life among the poor black and white. They could hardly imagine a country in which people so different from themselves could be equal citizens. Contempt is easy to come by.

Humiliating and then re-humiliating The Other may be the single most dangerous secular political practice, one that calls for spiritual humility such as Lincoln’s.

How did Lincoln come to be this way? The element of silence was immense in the making of Lincoln. We will not understand his spiritual life of Lincoln if we don’t begin there. It is cosmos not history that is our frame of reference. This is an unusual perspective, but spiritual knowledge emerges from the same formless void that opens the book of Genesis. Born into that world, Lincoln’s inner life began.

Lincoln then held onto that silence throughout his life. In reminiscence after reminiscence, as we have seen in that big red leather book, those who knew him personally remark how he began their meeting with an extended silent listening.

Silence was not a technique with him, it was his spiritual practice.

This is Duncan Newcomer, and this has been Quiet Fire. The spiritual life of Abraham Lincoln.

.

.

.

Care to Enjoy More Lincoln Right Now?

Care to Enjoy More Lincoln Right Now?

GET A COPY of Duncan’s 30 Days with Abraham Lincoln—Quiet Fire.

Each of the 30 stories in this book includes a link to listen to the original radio broadcasts. The book is available from Amazon in hardcover, paperback and Kindle versions. ALSO, you can order hardcover and paperback from Barnes & Noble. In addition, our own publishing house offers these bookstore links to order hardcovers as well as paperbacks directly from our supplier.

.

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 4: The courage to say—’In spite of all this, I will be!’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 1: In this cruel month of death, what will be our legacy?

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 2: Coping with the Uncertainty and Mystery of a Deadly Disease

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 3: We Must Rise with the Occasion

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln: When will we be good? God knows!

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 6: Lincoln’s Courage to Judge and to Lament

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 7: Lincoln looks toward his spiritual hero, Washington

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 8: Four Score and Seven

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 9: A Unique Spiritual Quest and The Pilgrim’s Progress

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 10—When all three meet: Lincoln, black people and the Bible.

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 11—Raising a Flag and Contemplating the Sacred Pillars of America

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 12—Why do we refer to our most eloquent president as ‘Quiet’?

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 13—Ultimately, we are responsible for our faces.

- In Our Struggle for Freedom, the Truth is Not in Our Statues—It’s in Our Souls

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 16—In racial justice, ‘We … bear the responsibility.’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 17—Remembering Mrs. Keckley, a close friend who Lincoln realized he did not truly know

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln: Remember when a president’s 1st value was Kindness?

- Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 19—’The election was a necessity’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 20—’A Most Sacred Right’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 21—Locating the spiritual X-factor in Lincoln’s ground-breaking life

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 22—Lincoln shows us the power of holding even opposites together

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 23—The forest vision Lincoln shared with poet Rabindranath Tagore

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 24—Myths and wisdom in national conversation about rule of law

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 25—How a true leader expresses the nation’s grief

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 26—Choosing Humility over Humiliation

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 27—What shaped Lincoln’s soul?

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—Here’s to you Mrs. Robinson!

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—Now, we’re all hoping for ‘Yonder’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—In three words, he said it: ‘We are elected.’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—Let’s remember how he reached across the aisle to discover new friends

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—Marking the anniversary of those 272 words at Gettysburg

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—’The Last Best Hope of Earth’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—’A Christmas Carol’ with Abraham Lincoln