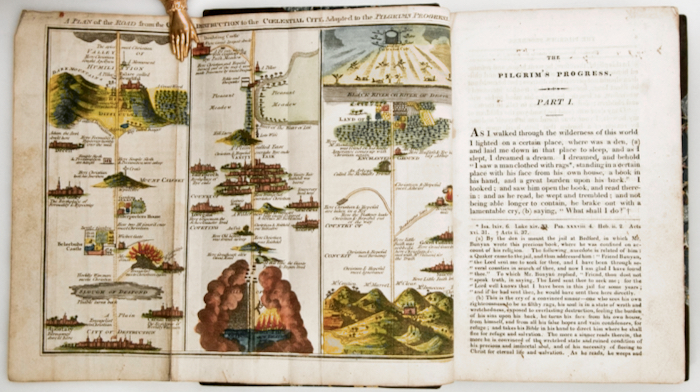

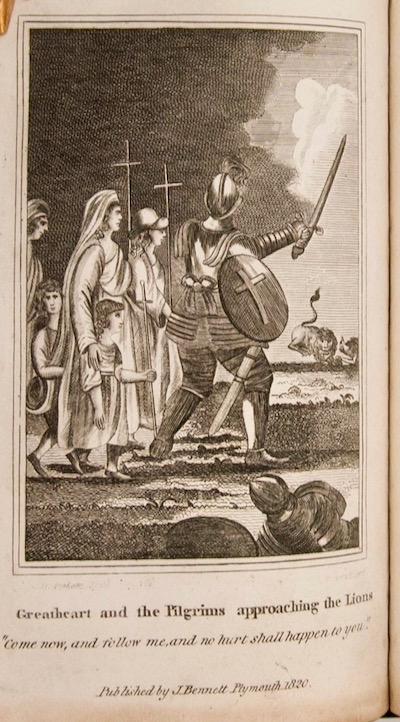

This 1820s edition of the original 1678 Pilgrim’s Progress was packed with vivid illustrations that would have caught the eye young readers.

.

By DUNCAN NEWCOMER

Host of the ‘Quiet Fire’ series

One of the black and white illustrations from that early 1800s edition of Pilgrim’s Progress. Lincoln surely would have found it an exciting tale.

This is Quiet Fire, a meditation on the spiritual life of Abraham Lincoln and its relevance to us today. Welcome. Here’s a Lincoln quote for you:

“That I am not a member of any Christian Church is true, but I have never doubted the truth of the Scripture; and I have never spoken with intentional disrespect of religion in general, or of any denomination of Christians in particular. … I do not think I could myself be brought to support a man for office whom I knew to be an open enemy of, and scoffer at, religion.”

Lincoln is running for Congress. It is 1846. His opponent is the Rev. Peter Cartwright, a locally famous Methodist evangelical preacher. Those rumors of Lincoln being a free thinking infidel have once again been raised. So, Lincoln responds with these words on a handbill to the Seventh District of Illinois. He wins the election 6,340 to 4,829.

As a young man, Lincoln sometimes was called an infidel. In the setting of New Salem, Illinois, that meant he and a few of his bookish friends held a wide variety of views. They were not orthodox Protestant Christian views. That does not mean he was what we might call an infidel today.

He could have thought, for example, that the Bible was not literally inspired, or that the miracles of Jesus were not scientifically factual, or that the Creation only took a week. And he did not want to join a church. Lots of infidel views.

Yet Lincoln was fiercely interested in the whole matter of religious and spiritual life. At that time he even wrote a deep essay on the anger of God that he shared with one of his older male friends.

Lincoln was inspired by Pilgrim’s Progress, the widely known and read book by the non-conformist preacher and writer John Bunyan. That 1678 book was well known even on the frontier. The hero, Christian, meets all sorts and conditions of people along the path of his spiritual progression. Lincoln would have liked that. He was one of those open-minded questers.

But some people in New Salem in 1830, if they had known, might have wondered about two other spiritual figures from history. Johnny Appleseed, for example. He was about to take his mission for God and orchards into the Great Lakes area of the American frontier. As a mystic unchurched preacher, would they think he was an infidel?

What about Joan of Arc, a saint so inspired by God that she moved a nation to crown a king as divinely ordained—and yet they burned her at the stake? What would they have thought of an untutored military genius and saintly Roman Catholic girl?

To grasp the wide reach of Lincoln’s spiritual life we can easily imagine him liking and wanting to know such spiritual heroes.

Johnny Appleseed was a common and a rustic man with an uncommon mission: to plant the mystical word of God and to seed hundreds of apple orchards and douse village sites throughout the expanding west. John Chapman, Appleseed’s real name, was a non-conformist as was John Bunyan.

In Pilgrim’s Progress, Christian, meets all sorts of people who influence his spiritual journey. Bunyan himself was a maker and mender of pots and kettles, a tinker. Like Johnny Appleseed and Lincoln, Bunyan had little formal schooling. Yet he had great faith struggles and extraordinary language skills. John Bunyan was often thrown in jail for his non-conformist preaching. He had rugged endurance as did Lincoln and Chapman.

These three men were great walkers and talkers, men of intense religious fervors and wide-ranging beliefs. Lincoln traversed on foot all of Sangamon County as a surveyor. Bunyan and Appleseed both were itinerant foot-bound preachers. While Bunyan was a mender of pots, Appleseed is often pictured wearing a cooking pot hat, not, of course, to be confused with Lincoln’s stove pipe hat.

Lincoln’s spiritual beliefs were similar to those of the iconic Johnny Appleseed. Both John Bunyan and John Chapman would easily have been close and kindred spirits to Abraham Lincoln in his early New Salem, Illinois, days. Shirt tail boys grown into rustic men with fervent faith and rhetorical skill.

Chapman was an evangelical follower of Emmanuel Swedenborg, himself an Enlightenment thinker, a mystic, and an inventor, among many other things. Swedenborg believed that God was peeking out through not only the Bible but also nature itself and through human reason.

These were beliefs Lincoln could agree with. Swedenborg also struggled with the existence of evil, such as war. He believed in universal salvation, as did Lincoln. He even had a belief in good angels that would meet each of us in heaven and bestow upon us the better angel of our own nature.

In the landscape of John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress we can imagine Lincoln meeting Johnny Appleseed, a frontier soul brother. We can also imagine him meeting a military and spiritual saint, that untutored young girl from the 1400’s Joan of Arc. Lincoln was always looking for an inspired fighting general who could lead the sacred national cause to victory.

Joan of Arc was a saint and like Lincoln she is hard to explain. How did such a mysterious figure ever come into history? No one, to this day, can explain how either of them came to be who they were.

At the end of his massive study of the life of that 15th century courageous young girl, Mark Twain himself concludes that we just cannot explain her. But Twain does write, on page 452 of his long-researched and passionately sincere historical novel Joan of Arc, that an artist who would paint Joan “should paint her spirit.”

Twain’s astonishment at the being of Joan of Arc rests on her pure and humble spirit and her bold unprecedented achievement for France against England. She lays the ground and the myths for the French nation. Her superhuman and even supernatural means of achievement led Samuel Clemens himself into a humble reverence, a new voice, without a trace of mockery or arch humor. He is as sincere as he will ever be in print.

Joan of Arc was a miraculous general and the fullest expression of obedient suffering and a noble, even holy, death.

Lincoln, however, had to find an able general in U.S. Grant, and then he left us with a nearly miraculous vision of a nation without malice toward the enemy, with charity for all and care for the wounded, and then his martyr’s death.

Lincoln was certainly no infidel. He was truly a John Bunyan type of pilgrim, with a nature so inclusive that he could be at home with these two remarkable religious figures.

In the torchlight of such a parade we too can be led down in honor even to the latest generation.

.

.

.

Care to Enjoy More Lincoln Right Now?

GET A COPY of Duncan’s 30 Days with Abraham Lincoln—Quiet Fire.

Each of the 30 stories in this book includes a link to listen to the original radio broadcasts. The book is available from Amazon in hardcover, paperback and Kindle versions. ALSO, you can order hardcover and paperback from Barnes & Noble. In addition, our own publishing house offers these bookstore links to order hardcovers as well as paperbacks directly from our supplier.

.

.

.

.

.

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 4: The courage to say—’In spite of all this, I will be!’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 1: In this cruel month of death, what will be our legacy?

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 2: Coping with the Uncertainty and Mystery of a Deadly Disease

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 3: We Must Rise with the Occasion

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln: When will we be good? God knows!

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 6: Lincoln’s Courage to Judge and to Lament

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 7: Lincoln looks toward his spiritual hero, Washington

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 8: Four Score and Seven

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 9: A Unique Spiritual Quest and The Pilgrim’s Progress

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 10—When all three meet: Lincoln, black people and the Bible.

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 11—Raising a Flag and Contemplating the Sacred Pillars of America

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 12—Why do we refer to our most eloquent president as ‘Quiet’?

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 13—Ultimately, we are responsible for our faces.

- In Our Struggle for Freedom, the Truth is Not in Our Statues—It’s in Our Souls

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 16—In racial justice, ‘We … bear the responsibility.’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 17—Remembering Mrs. Keckley, a close friend who Lincoln realized he did not truly know

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln: Remember when a president’s 1st value was Kindness?

- Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 19—’The election was a necessity’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 20—’A Most Sacred Right’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 21—Locating the spiritual X-factor in Lincoln’s ground-breaking life

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 22—Lincoln shows us the power of holding even opposites together

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 23—The forest vision Lincoln shared with poet Rabindranath Tagore

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 24—Myths and wisdom in national conversation about rule of law

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 25—How a true leader expresses the nation’s grief

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 26—Choosing Humility over Humiliation

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 27—What shaped Lincoln’s soul?

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—Here’s to you Mrs. Robinson!

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—Now, we’re all hoping for ‘Yonder’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—In three words, he said it: ‘We are elected.’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—Let’s remember how he reached across the aisle to discover new friends

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—Marking the anniversary of those 272 words at Gettysburg

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—’The Last Best Hope of Earth’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—’A Christmas Carol’ with Abraham Lincoln