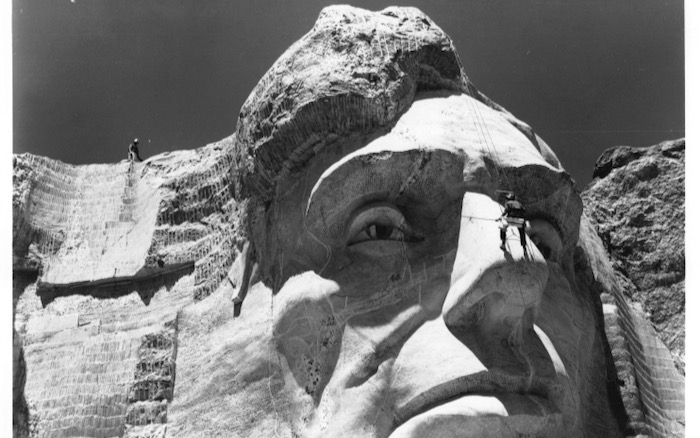

FINISHING LINCOLN’S NOSE—Between October 4, 1927, and October 31, 1941, Gutzon Borglum and 400 workers sculpted the 60-foot-high carvings of United States Presidents George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Theodore Roosevelt and Abraham Lincoln to represent the first 130 years of American history. As a result, we can argue that Borglum may have known more about the lines and shadows in Lincoln’s face than anyone else. After all, Borglum actually “lived” on that face for a very long time.

.

By DUNCAN NEWCOMER

Host of the ‘Quiet Fire’ series

This is Quiet Fire, a reflection on the spiritual life of Abraham Lincoln and its relevance to us today. Welcome.

When we call Abraham Lincoln the soul of America, which I do in my book 30 Days with Abraham Lincoln, we enter into a powerful process of discerning not only the meaning of Lincoln’s life. In exploring his life—we are peering deeply into our own.

That’s what The New Yorker staff writer Adam Gopnik argues he is doing in a long reflection on Lincoln in the magazine’s current issue. Gopnik charts how different eras of biographers have reinterpreted major themes in Lincoln’s life to find insights appropriate to their own needs. But therein lies the main flaw in Gopnik’s analysis. He keeps asking: What shaped these Lincoln biographers’ lives—or, we might say, what shaped their their souls as writers? Unfortunately, when he’s finished, Lincoln is more of a mystery than when he started.

So, let’s take a moment and ask the question Gopnik skips: What shaped Lincoln’s soul?

As we always do in Quiet Fire, let’s start with a quote—or, in this case, two short Lincoln quotes:

“All that I am or ever hope to be, I owe to my angel mother.” Psychologically, we all know mothers have a lot to do with our invention.

And then: “As I would not be a slave, so I would not be a master. This expresses my idea of democracy.”

Of course, we still have so many questions! Theologically, we want to know: What did Lincoln think God had to do with what he became? Politically, what about Lincoln can we find in these words to guide us now? Ethically, what values can we find in his declarations?

What can we discern from these two quotes?

In the spiritual life, and the psychological life, coming to a positive regard for your mother, or at least towards the Sacred Feminine, is a real goal. Most religions have a Holy Mother.

Lincoln sets such a goal for himself. He also probably meant that the genetic heritage of his mother, not his father, was the source of his genius. Several people in his time acknowledged the feminine in Lincoln. Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin thought that Lincoln’s steel-cable strength and yet tensile flexibility was—as she wrote in a newspaper column—his great feminine quality. In other words, he was not a rigid male authoritarian.

The man who photographed Lincoln the most, Mathew Brady, warned against photographing the left side of his face because, he said, it was too soft, dreamy and, of all things, too feminine.

The man who made the Mount Rushmore image of Lincoln, Gutzon Borglum, observed that mystic feminine side of his face, but did not, as a self-described “Western Man” like it as much as what he called his strong masculine right side.

However, in the spiritual life of Lincoln we move from thinking of him only in such psychological terms. Lincoln’s melancholy was not depression—it was spiritual. In that marvelous term of art from Elton Trueblood, it was his “theological anguish.”

The first title to Elton Trueblood’s ground-breaking book was Abraham Lincoln: Theologian of American Anguish. Trueblood wrote over 25 books and taught at Earlham College for years. This book was “rediscovered” and mentioned in the press by Nancy Reagan, which lead to its revival, and it is now available as Abraham Lincoln: The Spiritual Growth of a Public Man, via The Trinity Forum in McLean,Virginia.

Lincoln becomes more than a psychologically integrated and mature person, he has a spiritual extra added attraction. His life with his good mothers—and he had two, Nancy Hanks his Sweet Angel, and Sarah Bush Johnston, his strong step mother—takes him up to another level. From there he has a vision of humanity without malice and of people with charity for all. From there his sadness is sorrow, his grief is love’s loss, and his steadfastness is faith in Providence.

Such vision takes us to the second short quote: “As I would not be a save, so I would not be a master. This expresses my idea of democracy.”

His political spirit is right there. Where did Lincoln get his idea of democracy? Just as he moves from psychology to spirituality, he moves from politics to the ethical axiom of democracy: the law of equality. He would, he says, not want to be a slave.

He once said that as a boy he felt like a slave. But he didn’t want to become a master. Unlike so many people who solve the oppression and abuse of their childhood by becoming oppressors and abusers, Lincoln turned to a love of democracy, where people would aim to be legally equal with each other. Nobody, by law, above anyone else.

For Lincoln, people were not pawns in a game, people were the game. Of the people, by the people, for the people.

Lincoln did not try to divide people with anger, he tried to unite people with kindness, compassion really.

His political method was not to corner people in their hypocrisy, but to free people from their duplicity, to free America from its duplicity, freedom for some, slavery for some others.

Lincoln didn’t just invent the idea of democracy, nor was he the first to see democracy as a spiritual path toward the religious goal of a common wealth, a peaceable kingdom. Lincoln had ancestors who had a vision that the role of life was not to be the subject of a King, but a citizen of a community.

Lincoln never knew this but he had a great, great, great, great grandfather, Samuel Lincoln, who came to Hingham, Massachusetts, in 1637 to be a linen weaver. He came from Hingham, England. The folk in this eastern England area, called East Anglia, were radical Protestants, called by the dirty name Puritans. What was pure about these people was simply this: They wanted God, not a bishop; they wanted truth, not superstition; they wanted the Bible for themselves—and they wanted economic and political freedom from the King.

This idea, a vision of equality before God, rather than submission before a king or bishop travelled with the Lincolns to Massachusetts from England, and then with thousands of eastern English, down through New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Virginia, Kentucky and Illinois.

When Lincoln moved out of the legal servitude to his father at the age of 21 he moved to a little town with an English name, New Salem. There was a doctor there who had graduated from Dartmouth, and there was a cohort of free thinking folks who formed a debating society. Lincoln joined and wrote a paper on the anger of God, and some ideas from radical French philosophers.

But there also were tent meetings of evangelical Christians. Lincoln didn’t go but he caught the spirit, saw that people could be reborn. Even he would come to say a nation could be reborn in a new birth of freedom. That’s where the “people” come back into his political and spiritual vision.

The spiritual life of Lincoln seems to begin when we see him with his mother. But we also can say that it began for him generations back in the beliefs of his Puritan ancestors, beliefs that lit his eventual faith.

Lincoln invented himself not just from his favorite texts in Shakespeare and the Bible but from his mothers and God and his Puritan heritage and community ethic. So he was not just a self-made man after all.

As we re-invent democracy, American politics and faith, to look at how Lincoln re-invented himself can be a guide lighting a way in honor, down to the latest generation.

This is Duncan Newcomer, and this has been Quiet Fire. The spiritual life of Abraham Lincoln.

ReadTheSpirit magazine Editor David Crumm contributed to this week’s column.

.

.

.

Care to Enjoy More Lincoln Right Now?

Care to Enjoy More Lincoln Right Now?

GET A COPY of Duncan’s 30 Days with Abraham Lincoln—Quiet Fire.

Each of the 30 stories in this book includes a link to listen to the original radio broadcasts. The book is available from Amazon in hardcover, paperback and Kindle versions. ALSO, you can order hardcover and paperback from Barnes & Noble. In addition, our own publishing house offers these bookstore links to order hardcovers as well as paperbacks directly from our supplier.

.

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 4: The courage to say—’In spite of all this, I will be!’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 1: In this cruel month of death, what will be our legacy?

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 2: Coping with the Uncertainty and Mystery of a Deadly Disease

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 3: We Must Rise with the Occasion

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln: When will we be good? God knows!

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 6: Lincoln’s Courage to Judge and to Lament

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 7: Lincoln looks toward his spiritual hero, Washington

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 8: Four Score and Seven

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 9: A Unique Spiritual Quest and The Pilgrim’s Progress

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 10—When all three meet: Lincoln, black people and the Bible.

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 11—Raising a Flag and Contemplating the Sacred Pillars of America

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 12—Why do we refer to our most eloquent president as ‘Quiet’?

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 13—Ultimately, we are responsible for our faces.

- In Our Struggle for Freedom, the Truth is Not in Our Statues—It’s in Our Souls

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 16—In racial justice, ‘We … bear the responsibility.’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 17—Remembering Mrs. Keckley, a close friend who Lincoln realized he did not truly know

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln: Remember when a president’s 1st value was Kindness?

- Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 19—’The election was a necessity’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 20—’A Most Sacred Right’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 21—Locating the spiritual X-factor in Lincoln’s ground-breaking life

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 22—Lincoln shows us the power of holding even opposites together

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 23—The forest vision Lincoln shared with poet Rabindranath Tagore

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 24—Myths and wisdom in national conversation about rule of law

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 25—How a true leader expresses the nation’s grief

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 26—Choosing Humility over Humiliation

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire 27—What shaped Lincoln’s soul?

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—Here’s to you Mrs. Robinson!

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—Now, we’re all hoping for ‘Yonder’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—In three words, he said it: ‘We are elected.’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—Let’s remember how he reached across the aisle to discover new friends

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—Marking the anniversary of those 272 words at Gettysburg

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—’The Last Best Hope of Earth’

- Duncan Newcomer’s Abraham Lincoln Quiet Fire—’A Christmas Carol’ with Abraham Lincoln